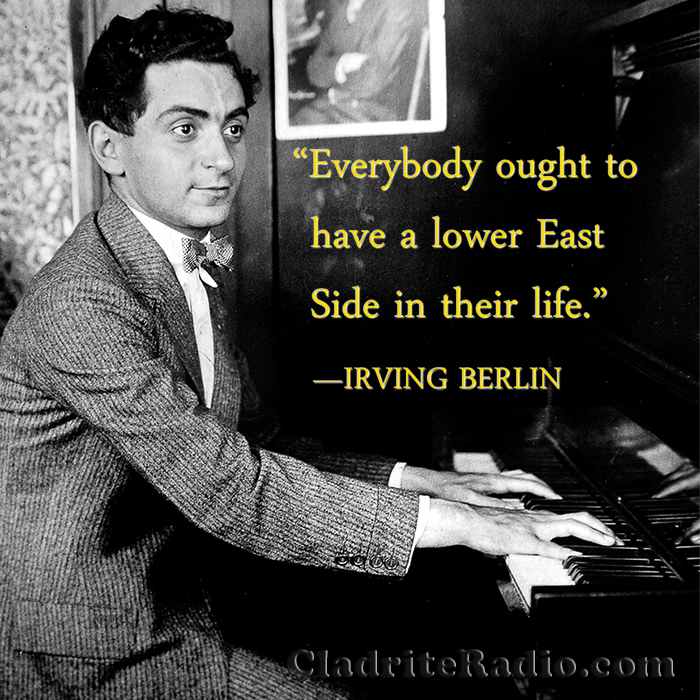

Here are 10 things you should know about Irving Berlin, born 133 years ago today. The great Jerome Kern once said of Berlin, “Irving Berlin has no place in American music—he is American music,” and we couldn’t agree more.

We’re featuring Berlin’s music, as performed by a variety of artists, all day today on Cladrite Radio. Why not tune in now?