Here are 10 things you should know about Charles Butterworth, born 124 years ago today. He’s one of those character actors of the 1930s and ’40s who made movie comedies that much funnier.

Tag: Chicago American

Happy 120th Birthday, Charles Butterworth!

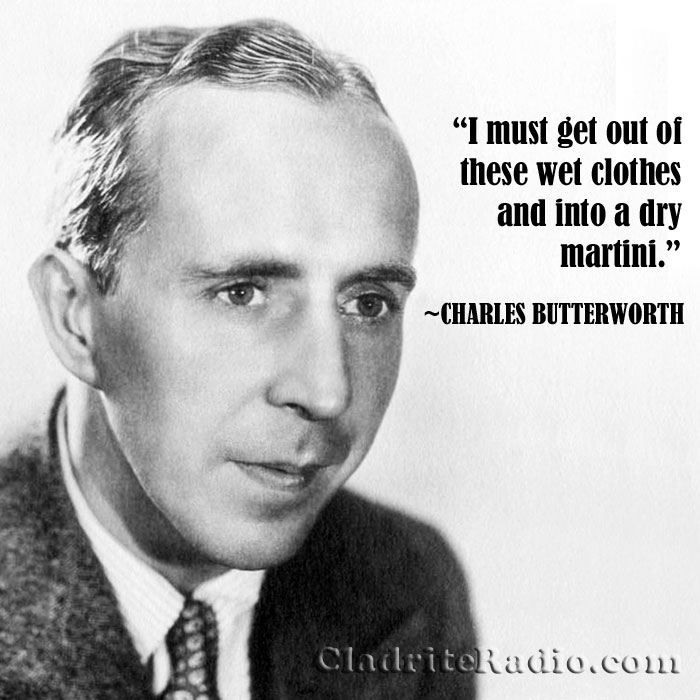

Charles Butterworth was born 120 years today in South Bend, Indiana. He’s in the rarefied company of greats like Roland Young, Charles Ruggles and Edward Everett Horton when it comes to making 1930s comedies just that much funnier. Here are ten CB Did-You-Knows:

- Butterworth earned a law degree from the University of Notre Dame, but never practiced, instead entering the journalism field.

- He worked as a journalist for the Chicago American. During those years, he established friendships with Heywood Hale Broun and humorist Frank Sullivan, who was instrumental in Butterworth getting radio work.

- When Butterworth first arrived in New York, he worked for the New York Times as a circulation department canvasser.

- Butterworth also worked as a secretary to author J. P. McEvoy, who was at the time writing the book for a musical called Americana. This gave Butterworth an entrée into the world of theater. He would go on to appear in several Broadway musicals of the 1920s, among them Allez Oop, Good Boy, Sweet Adeline and Flying Colors.

- His first credited film appearance (following a couple of brief, uncredited appearances) was in The Life of the Party (1930).

- Butterworth was known to be adept with humorous ad libs, so much so that some of the screenwriters he worked with in Hollywood came to rely on his ability to fill out an underwritten part with pithy lines of his own making.

- Butterworth was very close friends with fellow humorist Robert Benchley. Benchley is sometimes credited with the line quoted in today’s quote graphic, but he said Butterworth, who spoke the line in Every Day’s a Holiday (1937), but is said to have orginally ad-libbed the quip after falling into a pool at a party.

- Butterworth’s familiar screen character is said to have been the inspiration for cereal mascot Cap’n Crunch.

- He died in 1946 in a single-car automobile accident on Sunset Boulevard. It’s been suggested in some corners that his death was not accidental, that he was despondent over the passing of his pal Benchley some months earlier, but that’s not ever been proven.

- At the time of his death, Butterworth was engaged to actress Natalie Schafer, who would later be cast as Mrs. Thurston Howell III on the television sitcom Gilligan’s Island.

Happy birthday, Charles Butterworth, wherever you may be!

Times Square Tintypes: Ring Lardner

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles sportswriter, author, and playwright Ring Lardner.

HE’S FUNNY THAT WAY

RING LARDNER. He came to New York to do nothing and has been a failure ever since. Was born in Niles, Mich. The great event took place forty-six years ago. Always looks seven years younger than he really is.

Elmer the Great was his first play. While it was current he made his friends call him “Fanny.”

In the way of drinks his taste runs to any glass that is filled with anything but champagne. Champagne makes him nauseous.

As a newspaper man he worked in crowded offices with people talking and writing all around him. Today he can’t even begin to work if there is anybody else in the room.

He has never murdered anybody. If he does you can lay two to one that the party will be the author of a poem, story or play that is the least bit whimsical.

Occasionally he spends an entire day in a restaurant.

Was once paid five hundred dollars by a pottery concern to make a speech at their annual convention.

His first magazine story was about ball players. He sent it to the Saturday Evening Post. Not only did they buy the story but they encouraged him to write the now famous “You Know Me Al” yarns.

He’d rather be alone than with anybody excepting four or five people. He believes this is mutual.

Was among those who were the guests of Albert D. Lasker on the Leviathan‘s trial trip. While he was on the boat, he never saw the ocean.

Whenever he wants to laugh he goes to see Will Rogers, Ed Wynn, W. C. Fields, Jack Donahue, Harry Watson and Beatrice Lillie. If it is acting that he desires to see he hurries to a play with Alfred Lunt, Walter Huston, Lynn Fontanne or Helen Hayes. Otherwise he attends the opera.

He has flat feet.

Doesn’t care for parties. Unless he is giving them. Because then he can order as often as he likes.

Was fired from the Boston American in 1911. Went back to Chicago, his favorite shooting gallery, and asked the Chicago American for a job. The managing editor inquired: “What was the matter in Boston?” He replied: “Oh, nothing; except that I was fired.” The managing editor said: “That’s the best recommendation you could have. Go to work.”

Is the author of the following books: The Love Nest, What of It? How to Write Short Stories, Gullible’s Travels, The Big Town and a modest autobiography titled: The Story of a Wonder Man.

He can play the piano, the saxophone, the clarinet and the cornet. But not so good.

Has what is called “perfect pitch.” That is, he can tell which key anyone is singing or playing in without looking or asking. Once won $2 at this stunt. It really isn’t an accomplishment he can live on.

He is a passionate collector of passport pictures and license photographs of taxi drivers.

Among the things that annoy him are writing letters, answering the telephone, signing checks, attending banquets, untying the knot in h is shoelace, filling his fountain pen and trying to find handkerchiefs to match his neckwear.

Before he dies he hopes to write a successful novel. Believe he is going to live to a ripe old age.

Begins his stories with just a character in mind. Hardly ever knows what the plot is going to be until two-thirds through with the story.

He dislikes work (except the writing of lyrics), scenes like the Victor Herbert thing in the 1928 Scandals, insomnia, derby hats, beauty marks, motion pictures (excepting those Chaplin is in), dirty stories and adverse criticism—whether fair or not.

The W is for Wilmer.

He was standing at a bar in New Orleans during Mardi Gras time three years ago and a Southern gentleman tried to entertain him by telling how old and Southern and aristocratic his family was. Lardner interrupted the Southerner after twenty minutes of it with the remark that he was born in Michigan of colored parentage.

Recently he offered a cigarette concern this advertising slogan: “Not a Cigarette in a Carload.” They didn’t accept it.

He is noted for sending funny telegrams. One of the most famous is the one he sent when he was unable to attend a dinner. It read: “Sorry cannot be with you tonight, but it is the children’s night out and I must stay home with the maid.”