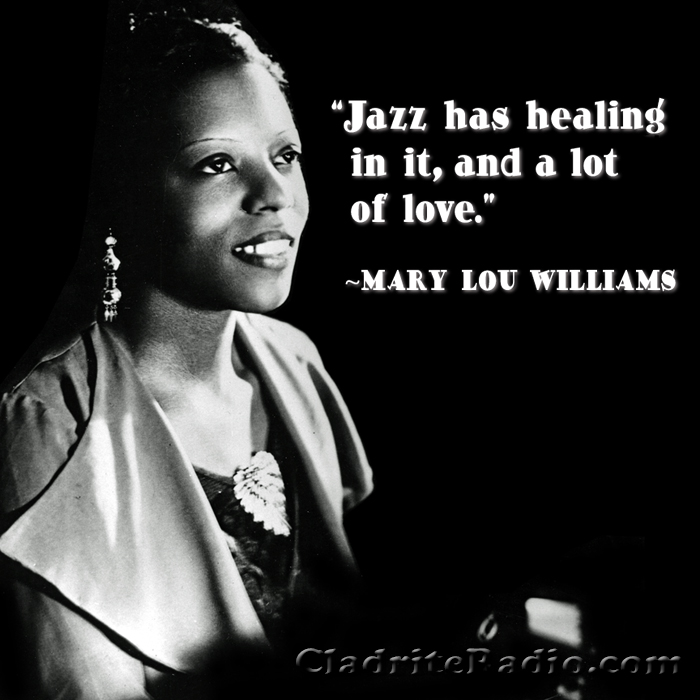

Composer, arranger and pianist extraordinaire Mary Lou Williams was born 106 years ago today in Atlanta, Georgia. Mary Lou’s mother and grandmother both worked as laundresses, but on the weekends, they drank heavily and argued. Mary Lou was a child prodigy on the piano, earning money to help support her family by entertaining at parties thrown by well-to-do white families.

As a teenager, she escaped the unhealthy home environment she’d grown up in, playing piano in traveling shows before settling in Kansas City in the late 1920s; it was an era when jazz music was dominated by men, and few were willing to give a young woman like Mary Lou a chance. Her husband, John Williams, was hired by bandleader Andy Kirk, and when Chicago record executive Jack Kapp came to town to audition local talent for the Brunswick label, Kirk’s usual pianist didn’t show. Williams, who had been touting Mary Lou’s abilities, convinced Kirk to give her a try.

Mary Lou was called and she rushed down to the club. The gig was a success, and Kapp arranged with Kirk for the band to do a recording session in Chi-town. The trouble was, when they arrived in the Windy City, they hadn’t brought Mary Lou with them, considering her just a fill-in. Kapp didn’t consider her a fill-in, though; he told Kirk there would be no recording with her. She was hastily summoned from Kansas City, and the session was a success.

With Mary Lou providing innovative arrangements and excelling in her role as featured instrumentalist, the Kirk Orchestra became more popular than ever. Eventually, Kirk and Williams began to butt heads as she continued to try to stretch out as a composer and arranger. She began to hear from other bandleaders—Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Cab Calloway, Benny Goodman, and Louis Armstrong, among them—asking her to do arrangements for them, and that perhaps understandably didn’t sit well with Kirk. For her part, Mary Lou felt underappreciated and underpaid, so she parted ways with Kirk and moved to New York, where Duke Ellington invited her to do arrangements for his orchestra.

That wasn’t a full-time gig, though, and Mary Lou was looking for her chance to shine. It came when jazz producer John Hammond arranged for her to be a featured performer at Café Society. She played there with just bass and drums as accompaniment, which required something of an adjustment on her part, after years of being a key cog in a big band. It was all on her now. Her run at the nightspot proved to be a success.

Though others of her generation rejected the innovations that came to be known as bebop, Mary Lou, ever looking to grow and stretch out, embraced them. “I tried to encourage the Modernists,” she said, “because I believed that bebop was here to stay.” This, even though she felt that many of the leaders of the new movement had borrowed from her work without giving her due credit.

Mary Lou’s NYC apartment became something of a salon where young jazz musicians would gather. She was willing to serve as something of a mentor to these young up-and-comers. She even wrote a song, In The Land of Oo-Bla-Dee, that was a big hit for Dizzy Gillespie and his band.

Sadly, at this stage of her life, Mary Lou was associated in minds of many with an older style of music and she wasn’t able to secure a recording contract, though she had a popular radio show at the time. Inspired in part by Ellington’s groundbreaking jazz suite, Black, Brown and Beige, she aimed to have a series of piano sketches she’d composed, under the name The Zodiac Suite, performed by an orchestra, and she succeeded: In 1946, an historic performance of the suite was undertaken at Carnegie Hall. But the reviews were not positive: It seemed the critics viewed The Zodiac Suite as neither fish nor foul, neither jazz nor classical.

So Mary Lou Williams, like many African-American jazz musicians before her, looked to Europe, but unlike many who preceded her in taking their talents overseas, Mary Lou found no satisfaction there. She returned to NYC and holed herself up in her apartment, putting aside music altogether as she dealt with emotional and mental distress.

As she put it, “Music had left my head.” She began to experience bad dreams, which she tried to interpret through drawings. She felt frightened when she began receiving messages from comic books, television and radio. “One day,” she said, “I heard a sound, like, ‘Go and purchase a rosary.’ I wondered what was happening; yet, I followed my sound to a Catholic church and started wailing madly. I was 44 years old and never asked God for forgiveness.”

Mary Lou found solace in the church—a “feeling of eternity,” as she put it. She joined St. Francis of Xavier church, where she met Father Anthony Woods, who encouraged her to return to her music. “Mary, you’re an artist,” he told her. “It’s your business to help people through music.” Father Woods asked Mary to consider writing a mass, and she was energized by the concept of combining her faith with her gift for music.

That request from Father Woods led Mary back into her music, and she experienced a renaissance in her career, finding herself in demand again.

Mary Lou Williams passed away from cancer in 1981, at the age of 71. She had arranged and composed more than 350 pieces of music.

Happy birthday, Ms. Williams, wherever you may be.