When browsing a flea market, antiques store, or the vintage corners of the internet, we love stumbling upon a product we never knew existed.

When browsing a flea market, antiques store, or the vintage corners of the internet, we love stumbling upon a product we never knew existed.

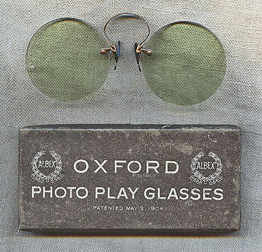

Ever heard of photo play glasses? Neither had we, until we came across the pair pictured here.

But what the heck are they, we wondered?

Our initial guess was that perhaps, in the early days of the motion picture industry, there was concern that watching movies might be bad for one’s eyes, the old “fear the new technology” gambit that’s still in play today.

This concern might have been sincere (if misguided) or ginned up by the vendor just to move some spectacles, but it wouldn’t surprise us if it existed.

So we turned to the experts over at Nitrateville.com, an online community of cineastes, collectors, and historians that we enjoy paying a visit to now and again.

Jack Theakston, assistant manager of the Capitol Theatre, a gorgeous 1928 movie palace in Rome, N. Y., offered the suggestion that the glasses were meant not to protect the eyesight of moviegoers, but of actors. In the early days of movies, Theakston said, UV-intensive klieg lights were used to illuminate the set, and actors often suffered a condition called “klieg eyes.” He also pointed out that the patent mentioned on the carton the glasses came in was not awarded for a specific use for the glasses, but for their design.

It’s an interesting notion, that a product might be created for actors to wear between takes and when they were relaxing on the set, and we certainly weren’t in position to discount the idea altogether, but we continued to harbor a sneaking suspicion that this was a product meant for the general public, not for such a niche market. We can’t prove it; it’s just a hunch. But as Mr. Theakston pointed out, Albex, the manufacturer of the glasses, dealt in industrial glasses, such as welder’s goggles, and there are contemporary accounts from the time of actors wearing sunglasses on the set to protect their eyes.

So it’s hard to say for certain.

Mike Gebert, one of the admins at Nitrateville, questioned whether the name “Photo Play Glasses” would have meant very much to the average person in 1904 (the patent date printed on the box), given that movies were in a truly nascent stage then. But upon closer inspection, he guessed that ’04 was just the date of the design patent, that the glasses themselves dated from the 1910s or even the ’20s.

His reasoning? The font on the packaging is, he says, Copperplate Gothic, which was designed in 1901. Given that fonts tend to take a while to come into popular use, he felt confident that glasses were marketed later, at which point motion pictures—photo plays, if you will—were certainly popular enough to inspire the marketing of such products.

Which kind of supports our theory, seems to us.

However, a poster from Australia named Brooksie did a little digging and learned that concern over kleig eyes was at its peak in the mid-to-late 1910s and came across suggestions that it was actors wearing shades, to use the modern vernacular, to protect their eyes from the bright lights on set that made sunglasses popular in the first place.

Which sort of leads us back to the idea that these were an industrial product, one meant for people working at making movies and not for the general public. The fear that watching movies could hurt one’s eyes may never have existed at all, except in our imagination. In any case, we’ve not turned up any solid evidence of it.

And we might well ask ourselves why we’re resisting the notion that it was actors and other filmmakers who wore Albex’s Photo Play Glasses, anyway. After all, if that’s the case, while we can’t know who owned the pair that came into our possession, we can have a good deal of fun imagining who might have possessed them. Perhaps they were once the property of Mary Pickford, John Barrymore, or even—be still, our hearts—Buster Keaton. They were all acting in movies by the 1910s, with Keaton the last of the three to the Hollywood party in 1917.

We’ll keep digging to see what we can come up with on this cinematic curio, but for now, perhaps we will allows ourselves to imagine that we now possess an item once owned by one of the giants of silent cinema.

Who can say we’re wrong, after all?