Have you ever heard of the Black Swan record label? Neither had we (and it’s not something we’re proud of, given we’re all about pop and jazz of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s), but we were intrigued by Michael Pollak’s recent story in the New York Times and felt the Cladrite community might find it of interest, too.

Have you ever heard of the Black Swan record label? Neither had we (and it’s not something we’re proud of, given we’re all about pop and jazz of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s), but we were intrigued by Michael Pollak’s recent story in the New York Times and felt the Cladrite community might find it of interest, too.

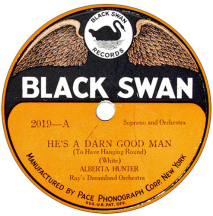

Black Swan was the first major black-owned record company. It managed to remain in operation for just a couple of years, but its influence was wide-ranging and long-lived.

Black Swan was founded by one Harry H. Pace, a banking and insurance worker and disciple of W. E. B. Du Bois, who had previously paired with W. C. Handy in forming the Pace & Handy Music Company, a music publishing concern.

Nine years later, Pace made history when he parted with Handy and started Black Swan Records. Many of the established labels at the time would not record African-American performers, but Pace was not satisfied with merely rectifying that injustice, he set out to demonstrate the breadth of the talent in the African-American community, to, as Pollak writes in the Times, “challenge white stereotypes by recording not just comic and blues songs, but also sacred and operatic music and serious ballads.”

Black Swan would have achieved a certain degree of importance if only because the great Fletcher Henderson played piano on many of the label’s early recordings, but Black Swan rose to greater heights in signing Ethel Waters. Her blues recordings made a splash, and a vaudeville tour featuring Black Swan artists managed to make the label what Pollak terms “a national one.”

But Black Swan’s success led more established labels to realize what they’d been missing in not recording black artists, and in an effort to elevate the nation’s image of African-American performers, the label opted not to sign blues singer Bessie Smith to a contract.

That was a costly mistake.

The label did introduce the likes of Waters, Henderson, Trixie Smith and Alberta Hunter, but after only two years, it was relegated to the dustbin of American music history. But during its brief existence, it had, as Pollak notes, awakened the music business, an impact that is still being felt today and for which we are all the richer.