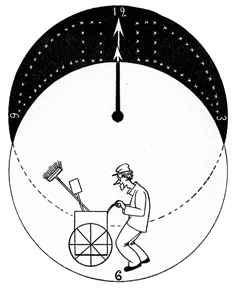

BROADWAY CHRONOMETER

| 10:30 A. M. | Broadway yawns. Actors in their sleep wake to rehearsals. Some poor nut has a song hit that no one will take off his hands. Ham and eggs at Childs’. Countless actors who believe that today their break may come. Press agents are going to what they call work. Broadway yawns again. Part of it goes back to sleep. The other part marches. They don’t make a dent. The Street still belongs to the foreign invasion. School kids and people out of work standing in line to get into the Paramount at the cheap morning prices. The afternoon papers begin to appear on the newsstands. Sounds of a jazz band practicing. It annoys the realtor two blocks away. In a couple of weeks he’ll pay to hear the same band and call it amusement. Dreary-eyed coryphées leaving side street hotels to hurry to rehearsals. The rouge and lipstick are the only thing genuine about them. They could put that on in their sleep. Don’t you worry, they’ll be repaid. Have their name in lights, get a husband, or else. Yawn, Broadway, but put your hand over your mouth. |

| 2 P. M. | Broadway is waking up. The light, the air, the sunshine is foreign. Matinée crowds now fill the streets. Actors are going to work. Why do they have matinées? You ought to see the same show some night that you saw in the afternoon. Where do people get the time to go to theaters in the afternoon? Why don’t they sleep? Actors are going to matinées. To see how they would have played the part or to applaud a fellow performer. A night club has a rehearsal in the cellar. Work all night and work all day. It’s a racket. Some people find heaven in a dive. Producers having their breakfasts. Big business deals written out on tableclothes. Do you know who’s in town? Four guys are spilling the same exclusive inside story. Gray’s is filled and Cain’s is making room for another show. Broadway is waking up. Theatrical folks are hurrying to their doctors. To their dentists. To take a sun-ray bath. Must keep in good condition. What’s the daytime for? The curtain’s going up. More jazz bands are rehearsing. Someone just signed a big contract and is going to get his name in lights. What the hell good is daytime? You can’t see your name in lights. Come on, Broadway, wake up. Get hot. Get dark. |

| 7:30 P. M. | It’s getting dark on old Broadway. Its getting hot on old Broadway. Actors answering the 7:30 call of the theater. Grease paint. Bring in that latest shipment through the back door, will you? She’s meeting him in front of the Rialto. It’s an opening night down the street. Maybe they’ll holler, “Author, author.” He’s invested everything in this one. Gee, I hope he clicks. He’s a nice guy. The critics. I’d like to see one of them write a play. Bernard Shaw? I mean a New York critic. Someone just cracked a gag. Lights are flickering. Someone else just cracked the same gag. Horns are tooting. Someone just had a reputation shattered. A new one tomorrow. The sky is beautiful. In some part of the world people are looking at the moon. It’s getting dark on old Broadway. It’s getting hot on old Broadway. No one can see above the electric light. Loan it to me and I’ll pay you back tomorrow. I haven’t got it myself. They’re all friends. All buddies. Just trying to do each other a good turn if it will benefit themselves. She’s with another guy tonight. Don’t know how she can keep up the pace. There goes the curtain. First nights. Glory seekers. Critics. Folks in search of amusement. Panhandlers. Bums. Noise. Lights. Greed. Backslapping. Tomorrow’s papers. What you’re doing now doesn’t count. The present is of the past. Pretty important, aren’t you all? Ever walk through a graveyard? All tombstones read alike. Broadway is getting hot. |

|

AFTER MIDNIGHT |

Broadway is Broadway. Broadway is making whoopee. Prohibition is only for the non-drinkers. Nobody knows what day it is. Hey, waiter, this table! Policemen standing in hallways. Long lines of cabs. We won’t get home ’til morning. Don’t talk like that to him. Want to get bumped off? Clubs banging on tables. That’s applause. Applause that’s life to an artist. I’m telling you it’s a sure in the third race at Havana tomorrow. Mr. Whoosis, I want you to meet Miss Whatsis. Now I’ve got a scheme. Some guys get all the luck. Broadway is making whoopee. Evening dress and gorgeous gowns. She was beautiful two hours ago. Legs. Arms. Eyes. Desire. Fill it up again, I want to forget. Tell me things, will you? I want to listen. Bad music. Bad gin. Whirling bodies. Isn’t this fun? We’re having a great time. I feel dizzy. It’s getting stuffy. You’re not used to it. People who are only eating sandwiches and drinking coffee in plain restaurants. Talking dreams. Giving the ego an outlet. A good listener is a good friend. Stray lights in an office building. Strays walking up and down as if they were going places. Couples window-shopping in dark windows. A practically empty street car darting through the night. Folks quarreling. Breaking their hearts. Giving it to Broadway so it can be paved. The street is practically deserted. But this is what the hick in the stick believes is the real Broadway. This is Broadway making whoopee. |

He’s likely not aware of it, but

He’s likely not aware of it, but