Here are 10 things you should know about William Holden, born 104 years ago today. The handsome leading man gave the shortest acceptance speech in Oscar history.

Tag: William Holden

10 Things You Should Know About Gloria Swanson

Here are 10 things you should know about Gloria Swanson, born 123 years ago today. The oft-wed Swanson was one of the biggest stars of the silent era.

10 Things You Should Know About June Allyson

Here are 10 things you should know about June Allyson, born 104 years ago today. She made a career of playing girl-next-door girlfriends and wives.

The curtain is drawn on a great director

In February 2008, NYC’s Film Forum held a tribute to director Sidney Lumet, who died today at the age of 86. The celebration of Lumet’s life and career took the form of a two-hour Q&A, interspersed with clips from some of his most memorable films. We were lucky enough to be on hand, and we are pleased to offer, as a tribute to a very talented movie maker, our account of the evening.

In February 2008, NYC’s Film Forum held a tribute to director Sidney Lumet, who died today at the age of 86. The celebration of Lumet’s life and career took the form of a two-hour Q&A, interspersed with clips from some of his most memorable films. We were lucky enough to be on hand, and we are pleased to offer, as a tribute to a very talented movie maker, our account of the evening.

Lumet shared in the early part of the discussion that his father, Baruch, was an actor in the Yiddish theatre, and Sidney himself got his start there at a very early age.

Lumet went on to appear in a number of Broadway shows, among them a Max Reinhardt production, before slipping behind the camera as a television director in the 1950s.

So it was fitting that the evening opened with a clip from One Third of a Nation (1939), which boasts Lumet’s only film acting appearance. The then-14-year-old director-to-be starred as the nephew of Sylvia Sidney.

The next clip shown was from the first movie he directed, Twelve Angry Men (1957). Asked if he’d made a specific effort to make the film in a cinematic style, so as to prove to the industry bigwigs that he could direct as well for the large screen as for the small, Lumet admitted with a laugh, “I was too arrogant. It never occurred to me that I might need to convince anyone.”

Asked later about working with Henry Fonda, Lumet said Fonda was constitutionally unable to make a false or dishonest move as an actor. “I don’t think he could’ve done it if I’d asked him to,” Lumet said. “He could only play the truth.”

Lumet said that filming on Twelve Angry Men was completed in 19 days. He said he shot the film in a very particular way. There were three levels of lighting in the film—sunlight through the windows, cloudy skies, as a storm approached outside, and with the overhead lighting in the jury room illuminated once the storm is underway.

Lumet shot the film entirely out of sequence, rotating around the room, getting each shot he needed from each actor under that particular lighting. Once he’d shot all of his sunlit shots, Lumet had the set relit to suggest cloudy conditions and slowly worked his way around the room again, going from character to character, getting every shot he needed.

Finally, he had the set relit once last time, with overhead lighting lit, and made the rounds again.

Lumet said he never used storyboards, as Alfred Hitchcock was famous for doing. Instead, he preferred to rehearse his actors for two weeks, as if they were mounting a play, and when he had all the blocking down, then he considered where to place the camera in each scene.

Read More »

Past Paper, pt. 4: The Brown Derby

Few things spark our interest (or a sense of yearning and regret at having missed them) as much as postcards, menus, and other memorabilia from once-popular and prominent eateries and night spots that exist no longer.

Here in NYC, there are (or, rather, were) such legendary dining and drinking establishments as the Stork Club, Jack Dempsey’s, Cafe Society, Luchow’s (the worst of it, in this case, is that we could have patronized Luchow’s when first we moved here, but what did we know?), the Copacabana, El Morocco, the Latin Quarter. Thankfully, we’ve still got Bemelmens, the Cafe Carlyle, the 21 Club, Sardi’s, the King Cole Bar, Keen’s, Fedora, McSorley’s—all but one of which we’ve patronized—but it’s all too tempting to focus more on what’s lost than on what remains.

Los Angeles has more than its share of fun culinary and night spots that are still going strong, too: The Frolic Room, the Formosa Cafe, Musso and Frank, Phillipe’s, Pink’s, Clifton’s Cafeteria, Miceli’s, Canter’s, Nate ‘n Al’s—all of which we’ve patronized (and will again). It strikes us odd as we write this that the historic places that remain in Los Angeles—the ones we’ve patronized, anyway—tend to be inexpensive and casual, while most of the venerable spots in NYC, McSorley’s and Fedora aside, are on the tony side.

But as with NYC, the list of L.A.’s gone-but-not-forgotten boîtes and beaneries is a long one. We’d give our eyeteeth to dine at Romanoff’s, Chasen’s, Preston Sturges’ the Players, or Thelma Todd’s Sidewalk Cafe or to cut a rug and sip a cocktail at the Cocoanut Grove, Ciro’s, The Mocambo or the Cafe Trocadero, but perhaps most of all, we’d love to hole up for an evening at the Brown Derby.

When we were kids, it was the Brown Derby that we read about, that was depicted on television (perhaps most famously in a memorable episode of I Love Lucy that guest-starred William Holden), that sparked our imagination.

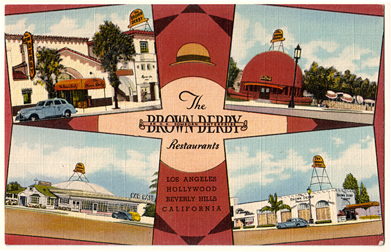

The Derby in all its incarnations is long-gone, alas, so we’re left to settle for mementoes of an establishment we never experienced first-hand, like the postcard below:

hi-res view |

It was the hat-shaped restaurant on Wilshire, seen in the upper righthand corner of the postcard, that was the original Brown Derby, by the way, and that’s the one we most regret not seeing, but the blog Dear Old Hollywood suggests that it was the Vine Street location (the one on the upper left) that was the most popular, because it drew more of the day’s celebrities, which is what drew many of the patrons to the restaurant. We’d happily accept a lift in a time machine back to any of the four locations, and in just about any decade—the 1930s, the ’40s, the ’50s, we’re not choosy.

By the way, we’d love to hear from you folks in Southern California (or just about anywhere else, for that matter) about any classic restaurants and bars we might have missed in our travels. Share!