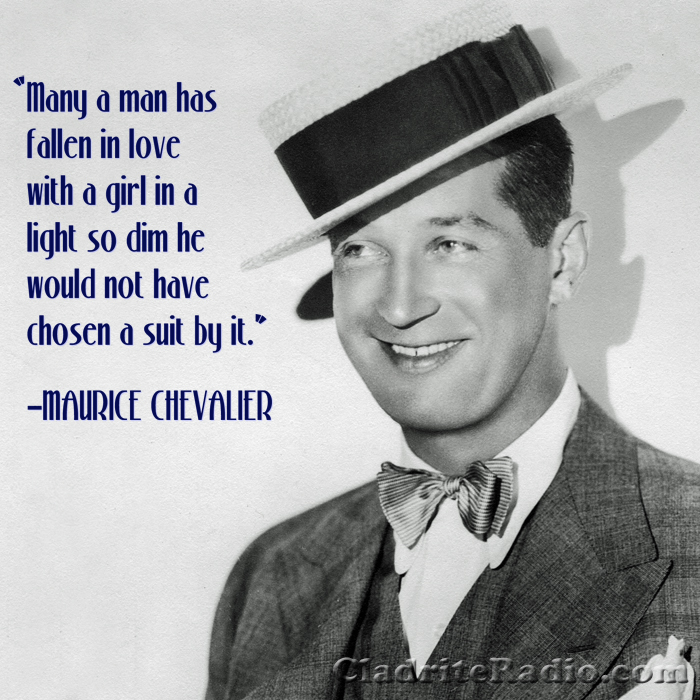

Actor, singer and rake Maurice Chevalier was born 128 years ago today in Paris, France. Here are 10 MC Did-You-Knows:

- Chevalier began his show biz career at age 13, singing in a local cafe.

- At 27, Chevalier was involved briefly with an performer named Fréhel, among France’s biggest stars of the day. She helped him get his first major role, in a show in Marseille called l’Alcazar, for which his critical notices were very positive.

- Chevalier once served as sparring partner to former light heavyweight champion of the world, boxer Georges Carpentier.

- Chevalier spent two years as a prisoner of war in Germany during World War I.

- Chevalier moved to London in 1917 and found success there at the Palace Theatre; he went on to make his Broadway debut in 1922 in the operetta Dédé.

- When talkies arrived, Chevalier headed for Hollywood, debuting in Innocents of Paris in 1929.

- By 1930, Chevalier had earned the only two Oscar nominations of her career, both in the Best Actor in a Leading Role category, for The Love Parade (1930), directed by Ernst Lubitsch, and The Big Pond (1930).

- In 1959, Chevalier was awarded a special Oscar for his half-century of contributions to the world of entertainment.

- Chevalier is said to have been very tight-fisted. When he was on contract with Paramount Pictures, he balked at the ten cents a day he was expected to pay for parking in the studio lot; he was able to negotiate a rate of a nickel a day instead.

- Chevalier’s accent in pictures was reportedly something of a put-on. He actually became quite fluent in English and spoke with only a slight accent. But he knew which side his croissant was buttered on.

Happy birthday, Maurice Chevalier, wherever you may be!

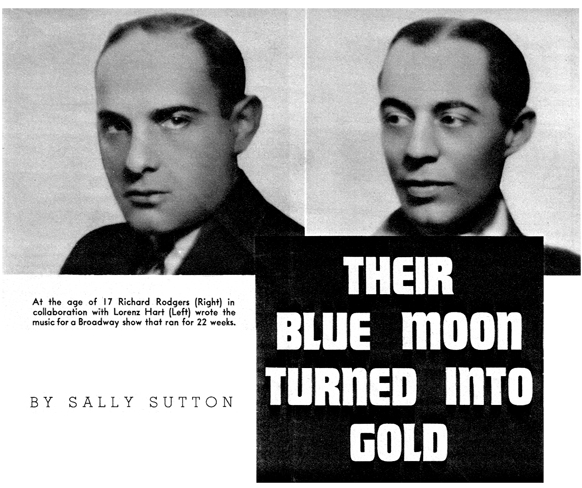

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.