We’ve come across any number of theatre flyers over the years (including the drive-in flyers from the late 1950s featured in this post), but we’ve never encountered one quite like this one.

|

|

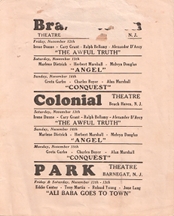

At first glance, it appears to be simply a promotional headshot of once-popular leading man Warner Baxter with a printed autograph (which is surprisingly convincing, by the way—we were briefly fooled into thinking we’d scored an genuine autographed photo of Baxter for a mere five smackers), but turn the photo over, and voila—it’s a programming schedule for three different New Jersey theatres. Part of the name is missing from the top theatre, but a little research has us convinced it was the Branchville Theater in Branchville, New Jersey. All we’ve been able to ascertain about the Branchville is that it was listed in the Film Daily Yearbook in 1944 and 1951, and on one weekend in 1937, they screened The Awful Truth, with Irene Dunne and Cary Grant, Angel with Marlene Dietrich, Herbert Marshall, and Melvyn Douglas, and Conquest, starring Greta Garbo and Charles Boyer.

How much earlier than that the theatre was in operation or when it closed, we can’t say. But we’d pay good money to see those three pictures at a small-town bijou like the Branchville, of that you can be sure.

Also featured on this promotional photo is the Colonial Theatre in Beach Haven, New Jersey. (Did you know that no fewer than ten Jersey towns had a theatre called the Colonial at one time or another? It’s true. And an eleventh burg, Hopewell, had a movie theatre called the Colonial Playhouse.)

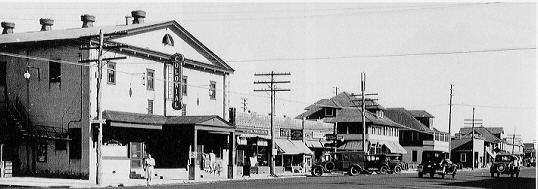

This Colonial opened in 1922 as the New Colonial on the corner of Bay Avenue and Center Street, replacing an old wooden structure some blocks away. One source says the old Colonial was retained and used in the winter, when the crowds thinned out (Beach Haven, as you might have guessed, is on the Jersey shore, so the population no doubt used to drop precipitously each year at summer’s end. Probably still does.)

Here’s a pair of then-and-now photos of the Colonial. Word has it, it’s now a private residence and no longer the hardware store it was in 2007, but we have no proof of that.

Interesting to note they were featuring the same three movies the Branchville was showing, but each played one day later at the Colonial. (We can’t help but wonder what the Colonial was showing on Friday, Nov. 12, 1937. The flyer doesn’t say.)

The last bijou on the flyer is the Park Theatre in Barnegat, New Jersey. Both the Barnegat and the Colonial (and, we’re guessing, the Branchville) were owned and operated by one Harry Colmer, who died in 1956. His family operated the theatres until 1964, when they sold them.

The Park, which opened in the early 1900s as the Barnegat Opera House, a venue for vaudeville and minstrel shows, began also showing movies between 1915 and 1920. It later became a full-time movie house under the new name. The Park Theatre, since demolished, was located on Shore Road in Barnegat, which is presently Route 9.

The weekend of Friday and Saturday, November 12th-13th, 1937, the Park was featuring Ali Baba Goes to Town, starring Eddie Cantor, Tony Martin, and Roland Young. That one we’d have to think twice about catching. We’d likely opt to drive the twenty miles over to Beach Haven to take in The Awful Truth or Angel at the Colonial (Branchville lies 142 miles away, a bit of a trek to catch a movie).