THE PRINCESS AND THE PEA

The boss rubbed Marie Dressler and got a balance in the bank.

The boss rubbed Marie Dressler and got a balance in the bank.

THE PRINCESS AND THE PEA

The boss rubbed Marie Dressler and got a balance in the bank.

The boss rubbed Marie Dressler and got a balance in the bank.OUR FIRST LADY STRIPS FOR ACTION

MARIE DRESSLER is the one woman whose name is in the date book as far back as 1925, who doesn’t give me a pain. I guess everyone likes her. Even these cats that come in here with gastritis every time somebody else makes a hit in a picture can stand the idea that Marie Dressler is knocking them dead with every release. Maybe it’s because Marie is nobody’s rival for a beauty prize. What really burns them up is having new cutie breeze into town hunting for a lap to climb on. Nobody got alarmed when Miss Dressler began squeezing through the doors of casting offices. And now it’s too late to do anything about it.

MARIE DRESSLER is the one woman whose name is in the date book as far back as 1925, who doesn’t give me a pain. I guess everyone likes her. Even these cats that come in here with gastritis every time somebody else makes a hit in a picture can stand the idea that Marie Dressler is knocking them dead with every release. Maybe it’s because Marie is nobody’s rival for a beauty prize. What really burns them up is having new cutie breeze into town hunting for a lap to climb on. Nobody got alarmed when Miss Dressler began squeezing through the doors of casting offices. And now it’s too late to do anything about it.THE WHAM WHAT AM!

If we could save and market what the actor bunch of Hollywood comes into this massage parlor to have slapped off, we’d put Armour out of business. … Well, I’ve got to turn on the radio—loud. Those are my standing orders. Whenever they begin to howl in the back room, cover up with music. I hunt over the dial until I get something with lots of music. … This tenor up in Oregon will do fine. There’s jazz for you!

If we could save and market what the actor bunch of Hollywood comes into this massage parlor to have slapped off, we’d put Armour out of business. … Well, I’ve got to turn on the radio—loud. Those are my standing orders. Whenever they begin to howl in the back room, cover up with music. I hunt over the dial until I get something with lots of music. … This tenor up in Oregon will do fine. There’s jazz for you! The late Jack LaLanne may have been the most famous and longest-tenured of celebrity fitness experts, but he wasn’t the first. Syvia Ulback, known in her heyday as both Madame Sylvia and Sylvia of Hollywood, preceded him by at least a decade.

The late Jack LaLanne may have been the most famous and longest-tenured of celebrity fitness experts, but he wasn’t the first. Syvia Ulback, known in her heyday as both Madame Sylvia and Sylvia of Hollywood, preceded him by at least a decade.

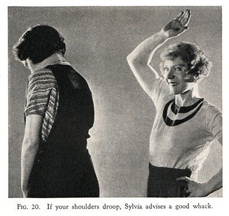

Sylvia’s beat was more beauty than fitness, but she knew full well that you can’t have the former without the latter, and she made certain her famous clients knew it, too. A masseuse by trade, Sylvia also advised her clients on proper diet and the importance of exercise.

Her client list amounted to a virtual Who’s Who of 1920s and early ’30s Hollywood, including Bebe Daniels, Ramon Navarro, Ronald Colman, Norma Shearer, Ruth Chatterton, Ann Harding, Norma Talmadge, Charles Farrell, Zasu Pitts, Constance Bennett, and Marion Davies.

Born in Norway in 1881 to artistic parents—her mother was an opera singer; her father an artist—Sylvia entered the field of nursing as a young woman. Having undergone massage training as well, she opened a studio in Bremen, Germany, when she was 18. In the early 1900s, she was wed to lumber dealer Andrew Ulback; the pair emigrated to the United States in 1921 when Andrew’s lumber business failed, settling first in New York City and Chicago before finally relocating to Hollywood in the mid-1920s.

Standing no taller than five feet, Sylvia once told The Hartford Courant that she had been inspired to pursue the reducing arts when she caught her husband eyeing a stenographer much slimmer than she. She adopted a painfully strenuous form of massage that she insisted would, when combined with proper diet and exercise, rid her clients of unwanted fat; though the claim may strike modern readers as dubious at best, the results she achieved were sufficient to ensure a quick rise for the ambitious masseuse.

Actress Marie Dressler was Sylvia’s first celebrity client, and her initial entree into that market depended entirely on garnering the approval of Dressler’s astrologer. Fortunately for Sylvia, she was given the okay.

Actress Marie Dressler was Sylvia’s first celebrity client, and her initial entree into that market depended entirely on garnering the approval of Dressler’s astrologer. Fortunately for Sylvia, she was given the okay.

Various stars came to so depend on Sylvia that they tried to monopolize her services. Mae Murray paid Sylvia to accompany her on a lengthy vaudeville tour (though Sylvia had to sue the actress for non-payment of salary upon their return to Hollywood—a suit she won), and Gloria Swanson was so impressed by Sylvia’s achievements that she arranged to have her hired by the Pathé Studio as the house masseuse at a weekly salary of $750, the rough equivalent of nearly $10,000 today. Joseph Kennedy, later patriarch of the famed Massachusetts political dynasty and then one of the studio heads at Pathé, hesitated to hire Sylvia at first, until she was able to diagnose his flat feet merely by watching him walk across a room.

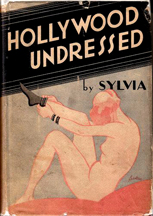

In 1931, Brentano published a best-selling volume entitled Hollywood Undressed: Observations Of Sylvia As Noted By Her Secretary. It was thought by some that the masseuse herself penned the memoir, which is filled with juicy tales of the Hollywood figures who made up Sylvia’s clientele, along with diet tips and exercise recommendations. In fact, the book was ghostwritten by screenwriter/reporter James Whittaker, first husband to actress Ina Clare.

Though—or, perhaps, because—the book broke the rules by telling tales out of school, it sold very well, but at a price. Sylvia had bitten the hand that fed her, and it hurt her standing in Hollywood. But she managed to limit the damage by adopting additional avenues of influence and income.

Though—or, perhaps, because—the book broke the rules by telling tales out of school, it sold very well, but at a price. Sylvia had bitten the hand that fed her, and it hurt her standing in Hollywood. But she managed to limit the damage by adopting additional avenues of influence and income.

Sylvia was soon writing syndicated columns on health and beauty for newspapers across the country and for Photoplay magazine; she also hosted her own nationally syndicated radio show, Madame Sylvia of Hollywood.

The radio show inspired a bit of a scandal when, in 1934, Sylvia, having aired an interview she said was with Ginger Rogers, was sued by the popular actress, who insisted that she had not taken part in any way in the broadcast. The case was settled out of court.

Sylvia also wrote three more bestselling books advising women on topics of health and beauty, this time with full author credit: No More Alibis (1934), Pull Yourself Together, Baby (1936), and Streamline Your Figure (1939).

On June 27, 1932, Sylvia, at the age of fifty, divorced Andrew Ulback. Just four days later, she married stage actor Edward Leider, eleven years her junior.

Sylvia abruptly retreated from the spotlight in 1939, enjoying a long life with Edward in relative obscurity. When she died, at age 94 in March 1975, just a month after Edward passed away, she was living in a small bungalow in Santa Monica. On her death certificate, her occupation was listed as “housewife.” Few, if any, publications noted her passing. Her influential career had been all but forgotten.

This story originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2011 issue of Zelda, the Magazine of the Vintage Nouveau. Watch this space next week for the first chapter from Sylvia Ulback’s Hollywood Undressed.

Some years ago, we had the pleasure of viewing Lonesome, a silent-talkie hybrid that was released in 1928. It’s not an easy movie to catch; as far as we know, the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, has one of the few extant prints. (Someone seems to have loaded Lonesome up on YouTube, and we suppose that’s better than not seeing it at all, but just barely.)

Some years ago, we had the pleasure of viewing Lonesome, a silent-talkie hybrid that was released in 1928. It’s not an easy movie to catch; as far as we know, the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, has one of the few extant prints. (Someone seems to have loaded Lonesome up on YouTube, and we suppose that’s better than not seeing it at all, but just barely.)

Lonesome could not be more charming. Its appeal is based in large part on the fact that much of it was filmed on Coney Island, and any glimpse of that magical setting as it was in the 1920s is to be treasured.

But the plot of the picture is engaging, too. It tells the tale of two lonely Manhattanites who experience a chance meeting at Coney Island and go on to spend a magical day together before getting separated that evening, with neither having learned the other’s last name. In a city of millions, will they ever manage to find each other? (If you think we’re going to tell you how it turns out, you can think again. No blabbermouths, we.)

Lonesome was originally released as a silent picture, but with all the fuss over the new sound technology, it was decided to bring back all involved parties to film three scenes with synchronized music and dialogue. So it’s not quite a silent and not quite a talkie.

But it’s certainly delightful, in our opinion, and we encourage you, if you ever have the opportunity, to see it (in a theatre and not streaming online, if at all possible).

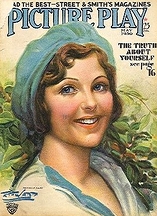

But you might well be wondering why we’re mentioning what is today a rather obscure picture now? Well, we’re sad to report that it’s because the movie’s leading lady, Barbara Kent, one of Universal Studios’ original contract stars and the final surviving WAMPAS Baby Star of 1927, died a week ago yesterday at the age of 103.

But you might well be wondering why we’re mentioning what is today a rather obscure picture now? Well, we’re sad to report that it’s because the movie’s leading lady, Barbara Kent, one of Universal Studios’ original contract stars and the final surviving WAMPAS Baby Star of 1927, died a week ago yesterday at the age of 103.

The Canadian-born Kent (her birthname was Barbara Cloutman) was not, admittedly, the biggest of names, even at the height of her career, but she made her mark, making eight or nine silents before successfully navigating the switch to talking pictures. She made 25 sound movies following her appearance in Lonesome, but retired from acting in 1935.

Among Kent’s most notable films were her screen debut in Flesh and the Devil (1926), with John Gilbert and Greta Garbo; a pair of starring roles opposite Harold Lloyd, in 1929’s Welcome Danger and Feet First a year later; a supporting role in Indiscreet (1931), which starred Gloria Swanson; and Emma, which featured Myrna Loy and Marie Dressler.

In the course of her nine-year career, Kent also worked alongside Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Richard Barthelmess, Edward G. Robinson, Charles “Buddy” Rogers, Andy Devine, James Gleason, Ben Lyon, Gilbert Roland, Noah Beery, Victor Jory, Dickie Moore, Monte Blue, Wallace Ford, Ward Bond, Arthur Lake, and Rex the Wonder Horse. That may not qualify as a Hall of Fame roster of co-stars, but many an actress has done worse.

In the course of her nine-year career, Kent also worked alongside Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Richard Barthelmess, Edward G. Robinson, Charles “Buddy” Rogers, Andy Devine, James Gleason, Ben Lyon, Gilbert Roland, Noah Beery, Victor Jory, Dickie Moore, Monte Blue, Wallace Ford, Ward Bond, Arthur Lake, and Rex the Wonder Horse. That may not qualify as a Hall of Fame roster of co-stars, but many an actress has done worse.

After retiring, Kent refused virtually all interviews about her years in Hollywood—one notable exception was the time she afforded author Michael G. Ankerich, who profiled Kent in The Sound of Silence: Conversations with 16 Film and Stage Personalities Who Bridged the Gap Between Silents and Talkies—as she settled into a successive pair of happy marriages—first to Harry Edington, a Hollywood agent, whom she wed in 1932, and then, some years after Edington’s death in 1949, she married Jack Monroe, a Lockheed engineer. Aside from evading would-be interviewers, Kent reportedly spent her free time in her golden years as a golfer and a pilot.

For more on Kent’s life and career, give this New York Times obit a look.