SAY IT WITH SONGS

Tag: Irving Berlin

Times Square Tintypes: George White

SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL

Times Square Tintypes: George Gershwin

“STRIKE UP THE BAND”

Play it again … and again

There’s a antique mall in an old farmer’s market building in downtown Oklahoma City that we try to get to whenever we’re home visiting the family, and in that mall is a particular store that we make it a point to patronize. The owner’s kind of an old grump and some of his stuff’s overpriced, but he has plenty of the sort of paper ephemera we like, and we usually find something to covet, if not purchase.

There’s a antique mall in an old farmer’s market building in downtown Oklahoma City that we try to get to whenever we’re home visiting the family, and in that mall is a particular store that we make it a point to patronize. The owner’s kind of an old grump and some of his stuff’s overpriced, but he has plenty of the sort of paper ephemera we like, and we usually find something to covet, if not purchase.

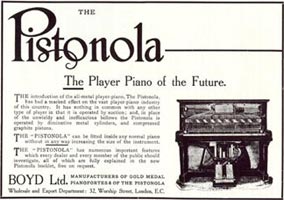

The last time we were in his store, we stumbled upon a shelf filled with piano rolls of the 1920s and ’30s, and our heart skipped a beat. They were much more reasonably priced than many of his other offerings, and the titles were right up our alley, many of them songs frequently heard on Cladrite Radio.

It’s one of the few regrets we have about residing in New York City: Space is at a premium, and we simply don’t have room for a player piano. Would that we did. We’d snap up a couple of dozen of that old grump’s piano rolls in a heartbeat

But we did recently learn of a YouTube channel that eases the pain a bit. AeolianHall1 is the poster’s handle, and his or her channel features a delightful roster of piano roll recordings from the 1930s, the 1920s, and even earlier.

We thought we’d share one of our favorites with you, Pauline Albert’s recording of Irving Berlin‘s 1927 hit “The Song Is Ended (but the Meolody Lingers On). But you really should make it a point to pop over and give AeolianHall1’s extensive collection a good listen.

|

A Berlin Parade

As a small Easter egg for the Cladrite Radio community, we thought we’d offer the following:

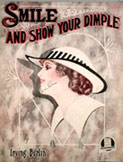

Did you know that the lovely Irving Berlin standard “Easter Parade” is a reworking of an earlier Berlin tune? It’s true. In 1917, Berlin wrote a song called “Smile and Show Your Dimple.” It was recorded by Sam Ash, recording artist and Broadway star (he also played dozens of bit parts in pictures), but that recording didn’t catch on with the public, so in 1933, when creating the score for the Broadway musical revue “As Thousands Cheer,” Berlin revisited the song, composing new lyrics and tweaking the melody a bit to create the song that is still so well known today.

Did you know that the lovely Irving Berlin standard “Easter Parade” is a reworking of an earlier Berlin tune? It’s true. In 1917, Berlin wrote a song called “Smile and Show Your Dimple.” It was recorded by Sam Ash, recording artist and Broadway star (he also played dozens of bit parts in pictures), but that recording didn’t catch on with the public, so in 1933, when creating the score for the Broadway musical revue “As Thousands Cheer,” Berlin revisited the song, composing new lyrics and tweaking the melody a bit to create the song that is still so well known today.

Just as a bit of trivia, “Easter Parade” was introduced in “As Thousands Cheer” by Marilyn Miller and Clifton Webb.

Just as a bit of trivia, “Easter Parade” was introduced in “As Thousands Cheer” by Marilyn Miller and Clifton Webb.

So we’re sharing a 1933 recording below of Webb singing the song backed by the Leo Reisman Orchestra, along with a 1942 Harry James rendition, a 1939 recording by the Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians, Bing Crosby singing the song backed by the Victor Young Orchestra in 1948, a Gene Austin recording from 1933, and Sam Ash‘s 1918 recording of the song that fostered “Easter Parade,” “Smile and Show Your Dimple.”

“Easter Parade” — Clifton Webb with the Leo Reisman Orchestra

“Easter Parade” — Harry James and His Orchestra

“Easter Parade” — Guy Lombardo and His Orchestra

“Easter Parade” — Bing Crosby with the Victor Young Orchestra