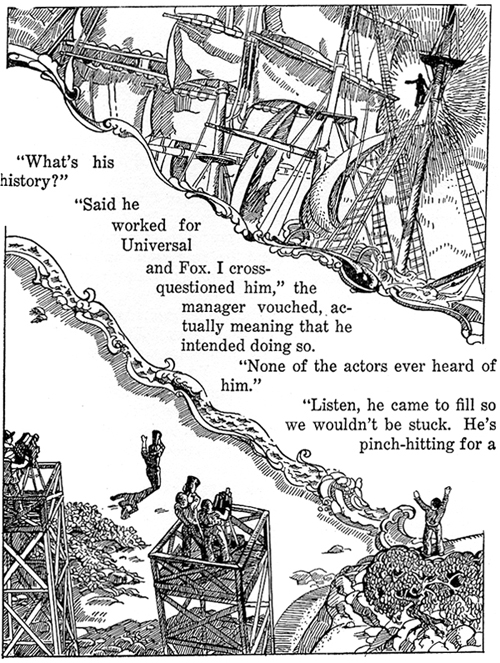

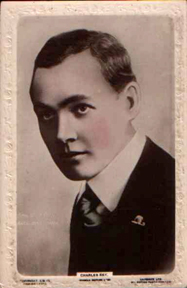

Charles Ray was a popular juvenile star in the 1910s and ’20s, but by the ’30s, his career was on the rocks, and he turned to writing. Here’s another in a series of offerings from his book, Hollywood Shorts, a collection of short stories set in Tinseltown.

Charles Ray was a popular juvenile star in the 1910s and ’20s, but by the ’30s, his career was on the rocks, and he turned to writing. Here’s another in a series of offerings from his book, Hollywood Shorts, a collection of short stories set in Tinseltown.