Here are 10 things you should know about Walter Kingsford, born 140 years ago today. He enjoyed success on stage and in radio, motion pictures and television.

Tag: George Bernard Shaw

Hollywood Undressed, Chapter Fourteen

The fourteenth chapter from Hollywood Undressed, a 1931 memoir attributed to the assistant of masseuse and health guru Sylvia Ulback, a.k.a. Sylvia of Hollywood (but actually ghost-written for Sylvia by newspaper reporter and screenwriter James Whittaker), tells the tale of how actress Grace Moore, upon her arrival in Hollywood, tried to knock Gloria Swanson off her Tinseltown pedestal.

THE PLOT THICKENS—AND SOME MIDRIFFS!

IT SEEMS that the first thing for a high-power beauty to do when she gets into the movies and comes to Hollywood si to go up and give Gloria Swanson a big shove and say: “Yah!”

IT SEEMS that the first thing for a high-power beauty to do when she gets into the movies and comes to Hollywood si to go up and give Gloria Swanson a big shove and say: “Yah!”I don’t know why this is, but they all do it. They don’t pick on Garbo, or Chatterton, or Shearer. No; they all come into town and go up to the hotel and wash their faces, and beat it out to Sunset Boulevard and Crescent Drive, where Gloria’s front lawn comes down to the sidewalk, and get out and walk up and down and sneer and yell: “Come out and fight! I can lick you!”

Why, even Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the London actress who is so veteran that she used to play for one of the Edwards—the VII, I think—even this old-timer had to get a rush of rivalry to her venerable head and take a fall out of Gloria. It was a rather nasty fall, too.

Mrs. Pat saw one of Gloria’s films and was all excited about it and went around Hollywood begging to meet “that perfectly charming gel.” And Gloria’s friends began to set up the drinks and celebrate, because Mrs. Pat knows Bernard Shaw and that makes her opinion worth its weight in salt. They threw a reception for the woman who has been the toast of London so long, and were tickled to death—until Mrs. Pat, who had been waiting for this spot, added to her honeyed flattery of Gloria the little bit of wormwood which she had been waiting to spill all the while.

“Yes, a dee-lightful creature, this Swanson girl; really a pippin, as you Americans say. You know, I’ve been wondering what it was that struck me most about that gel and her most striking smile, and I’ve just hit on what it is. Really, my dears, she ought to be told to file down her teeth!”

I GUESS the reason for all the resentment is Gloria’s pull with men. Other movie queens in Hollywood can give Gloria their arguments on picture grosses and the size of their fan mail, but Gloria’s front porch is the place where all the boys go on the night off. And Hollywood hostesses have learned not to give parties in competition with Gloria, because if they do, they only men they’ll get are local movie critics and assistants in the Hays office.

So the newcomers hear about this and decide that it’s about time to make a change. And they set out the drinks and the sandwiches, and put on the low-back gowns, and light up the front parlor and leave the shades up, and turn on the radio, and say to themselves: “This’ll fetch the boys.” And give a sigh for poor old Gloria and think that she’s going to be pretty lonesome up in that big old house when the sports get wise to the new attraction—but it serves her right for hogging the trade.

But the same thing happens every time. Along about midnight the newcomer puts the sandwiches in the ice box and crawls into bed and lies there wide awake for the next few hours, gnawing her knuckles and listening to the male chorus doing Sweet and Low in twelve verses on Gloria’s veranda.

Usually the newcomers calm down after a while and leave Gloria alone, figuring, who wants to take her bunch of amateur tenors away from her, anyway? But every once in a while a born scrapper comes to town who picks herself up after the first knockdown, shakes her head, and squares off to make a finish fight of it. Then Gloria, according to the rules of the game, has to put up her Most Popular Girl championship and accept the challenge.

Times Square Tintypes: The Marx Brothers

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles the Marx Brothers.

AH, NUTS!

THE MARX BROTHERS. They are known as Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Zeppo. Their real names are Julius, Arthur (formerly Adolph), Milton (editor’s note: Skolsky got this wrong: Chico’s real name was Leonard; it was Gummo who was named Milton) and Herbert. They were given their nicknames by a kibitzer at a poker game in Galesburg, Ill.

Three of them are married. Harpo, the unmarried one, has been on the verge of eight times. With eight different girls.

Have been known as “The Three Nightingales,” “The Four Nightingales,” “The Six Mascots” (in this act they were assisted by their mother and their other brother, Gummo, now in the cloak and suit business), and “The Four Marx Brothers.” The name of the act depended on how many of the family were in it.

Are nephews of Al Shean of Gallagher and Shean fame.

Groucho’s theatrical career started at the age of thirteen in a Gus Edwards “School Days” act. He was fired in the middle of the tour because his voice changed.

Harpo’s debut was made twenty-two years ago on a Coney Island stage. He was pushed on when “The Three Mascots” were playing there. He wore a white duck suit with a flower in his buttonhole. Frightened, he stood with his back to the audience an didn’t say a word until the curtain fell. Has yet to speak a word on the stage. After his début “The Three Mascots” was changed to “The Four Nightingales.”

After finishing a sandwich at a party, Groucho throws the plate out the window.

Chico is the business member of the quartet. It was he who arranged for their first appearance in a Broadway show.

Harpo was once a bellboy at the Hotel Seville. He earned an extra twenty-five cents a week from Cissie Loftus for taking her dog for a daily stroll. Chico played the piano in nickelodeons. Groucho drove a grocery wagon in Cripple Creek, Col. He had a burning desire to become a prize fighter.

Whenever they want to get out of an engagement Harpo fakes an appendicitis.

Their dressing room is always filled with visitors. Herbert Swope, Neysa McMein, Harold Ross, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun and Alice Duer Miller are nightly visitors when they have a show in town.

Chico will bet on anything. Merely say it is a nice day and he will say: “I’ll bet you.”

Harpo’s and Zeppo’s favorite dish is crab flakes and spaghetti. Groucho and Chico, on the other plate, are especially fond of dill pickles and red caviar.

The four of them play the stock market. That’s why they’re still in the show business.

Whenever Groucho wants to visit his broker he tells his wife he is going to play golf. He visits his broker attired in a golf outfit, carrying a bag of clubs.

Are always playing practical jokes. Annoy interviewers by pretending they are slightly deaf. Another gag is Groucho telling their life story. He stops at a certain point saying: “This is all I remember of my life. Chico knows the rest.” Chico continues with an entirely different story. He also stops in the middle, offers the same excuse, referring the interviewer to Zeppo, who continues the process until all four have told a different story of their lives.

Offstage Groucho, Chico and Zeppo occasionally wear glasses.

Zeppo is in the real estate business. He tries to sell property backstage.

Harpo is the best poker player of The Thanatopsis Club. Has won enough money from Heywood Broun to pay for young Heywood’s tuition fee through any college in the country. Is also a great croquet player. Often plays in Central Park for a thousand dollars a game.

Their grandfather was a noted strolling German magician. Their grandmother was also in the act. She played the “accompanying music” on a harp.

They failed to click only once. In a London Music Hall. The Englishmen booed and threw pennies on the stage. Groucho stepped to the footlights and told them they were cheap. He dared them to throw shillings. They made more money at the performance than they were paid for the week.

To Harpo every woman, regardless of her name, is Mrs. Benson.

Harpo can play any musical instrument. Chico plays the piano and harp. Groucho plays the guitar. Zeppo likes to listen to the radio.

Times Square Tintypes: Lynn Fontanne

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles Lynn Fontanne, Broadway actress and half of the storied theatrical team Lunt and Fontanne.

TELL ME, PRETTY MAIDEN

LYNN FONTANNE. She’s just a bird in a “Guilded” cage.

Was born in London. Her name was Lily Louise Fontanne. Changed the Lily Louise to Lynn because it sounded better.

Was born in London. Her name was Lily Louise Fontanne. Changed the Lily Louise to Lynn because it sounded better.Every morning for breakfast she has honey and rolls.

She has a wide smile, a throaty laugh and a robust sense of humor.

Lives in a triplex apartment in East Thirty-sixth Street. The pride of the apartment is a fireplace with an aluminum background. The telephone operator there has a list of the people she will speak to.

A woman, above everything else, she believes, should be fashionable.

During the World War she worked in London as an emergency chauffeur.

She met Alfred Lunt, her husband, during a rehearsal of Clarence. Entering to speak his lines to her, he tripped and fell at her feet. It could be said that he fell for her. Later he suggested that they rehearse in the open air. He took her riding in an open carriage through the park. He gave their scripts to the driver to read while he proposed to her.

Dislikes short dresses and never wore them when they were the style. Wears a blue smock in her dressing room or when idling around the house.

She can foot pedal an Ampico piano longer and better than anyone in this state.

Avoids going to parties. Always giving the same excuse: “I’m too tired.” An actress, she insists, should keep away from her public. She is fond of dancing but seldom does.

After the opening performance of Strange Interlude she slept for fifteen hours.

Her husband’s pet name for her is “Rich Lynnie” because she is always saving her money.

Doesn’t like tinned food and people who rub their hands together. Hates to wear stockings but does. Like to wear jewelry but doesn’t. Hates to write letters and seldom does.

When traveling she brightens up her hotel room with chintz curtains and window flowers which she buys at Woolworth’s.

Her great ambition in life is to be a writer of critical essays.

Changes her perfume weekly. Claims a change of perfume is a change of attitude.

Two years ago, knowing that she was to be operated on for appendicitis, she played through an entire performance against doctor’s orders. Her substitute wasn’t ready. And she didn’t want that show to miss a performance.

Other people call her husband by his nickname, “Bill.” She always calls him Alfred.

She visited her home town, London, last summer for the first time in ten years. She went into a glove shop. The clerk greeted her with: “Oh, how do you do. So glad that you’re back. You’ve been acting out in the colonies, haven’t you?”

Her favorite dish is broiled scallops.

Times Square Tintypes: A. H. Woods

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles theatrical producer A. H. Woods.

SAMUEL HOFFENSTEIN’S CREATION

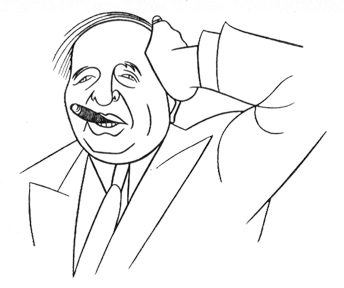

A. H. WOODS. His real label is Albert Herman. Without knowing a thing about numerology, he made his name initials. Then added the tag of Woods, taking it from N. S. Woods, an actor whom he worshiped.

Was a billposter. His real entry into show business was when he took a piece of lithograph paper to Theodore Kremer. Commissioned him to write a play about it. The picture was of the Bowery. Kremer had the measles at the time. The finished product was The Bowery After Dark.

His favorite combination of colors is yellow and black.

All his business correspondence ends with: “With Love and Kisses.”

Owen Davis used to write two plays a week for him. Still considers Bertha, the Sewing Machine Girl and Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model, the two best plays Davis ever wrote. Davis doesn’t.

Believes any play Samuel Shipman writes in Atlantic City is worth reading.

He hired his own Boswell in the person of Samuel Hoffenstein, who now does things in praise of practically nothing. Instead of recording the actual doings Hoffenstein allowed his imagination to write the life of Woods. Thus a character was created. One which he often tries to live up to. He believes what he read.

He sits with both feet resting on the chair.

Wore a dress suit only once in his life. It was at the opening of the Guitrys. He hired it for the occasion. Is very proud of the fact that Otto Kahn said he looked good.

He believes in luck and does most everything by hunches.

William Randolph Hearst practically produced The Road to Ruin for him without knowing it. Hearst gave him $500 to move out of one of his buildings. With this he started anew.

Will get up from his desk after a day’s work and depart for Europe with all the thought and preparation that you give to going to a movie.

Has made numerous trips to Europe with only a toothbrush in his pocket. While on the ship he occasionally worries where he is going to get the toothpaste.

He reads six plays a day. Will often buy a play by merely hearing an outline of the plot.

Once walked into Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater. Saw a pretty girl on the stage. Became quite enthused. Decided that a girl so beautiful deserved to be starred in a legitimate play. The girl was Julian Eltinge. He went through with it anyway.

Has a clay statue of a negro youth in his office for luck. In the hand of this youth he always places a copy of the script of his latest production.

Walter Moore is his best friend. For this there is a penalty. He is his companion on most of the sudden trips.

He uses the most profane language without quite realizing what it means. The rougher his language the better he likes you. When he talks pleasantly keep away.

His office is decorated with artificial flavors.

Every month he orders a thousand cigars. He chews a cigar more than he smokes it. Everybody always knows what part of the building he is in. He leaves a trail of ashes.

He knows George Bernard Shaw personally and calls him Buddy. There is no record of what Shaw calls him.

Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin worked for him before they entered the movies. He let them go because they wanted more money. He let them go because they wanted more money. Chaplin was getting twenty-five dollars a week and asked for thirty.

His favorite eating place is his office. Every day he has vegetable soup, apple pie and milk sent to him from the Automat. The actual time it takes him to eat this is one minute and twelve seconds.

In the summer he sits on a camp stool outside of his theater, the Eltinge, watching the audience enter.

A good script, he considers, is one that makes him forget his cigar has gone out.

During the rehearsals of The Shanghai Gesture, the cussing, hard-boiled Mr. Woods blushed and had the author tone down some of the lines.

Buttons are always missing from his overcoats.

Once considered producing Shaw’s Back to Methuselah. This play takes three days for one showing. He rejected it saying: “I’m too nervous. I’ve got to know the next day if I’ve got a hit.

At the foot of his desk there is a cuspidor. He generally misses.

He is afraid of the dark. He sleeps with the lights on.