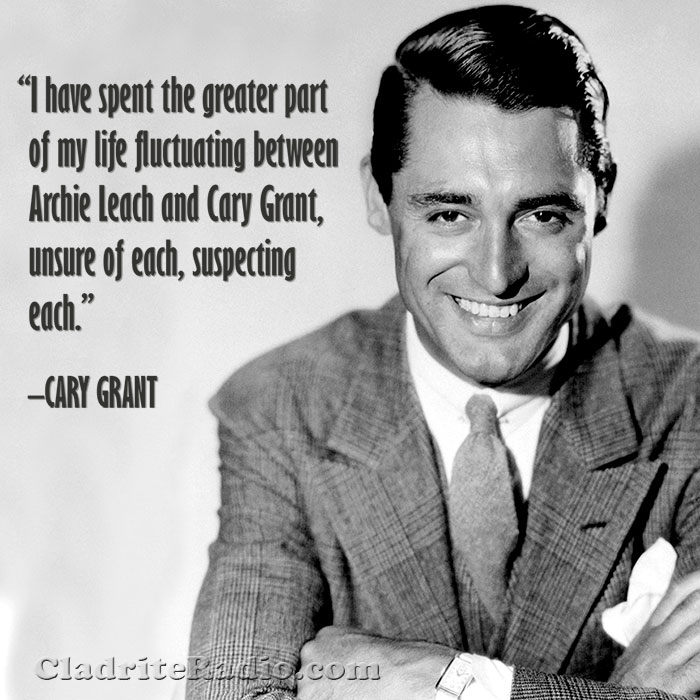

The great Cary Grant was born Archibald Alexander Leach 113 years ago today in Horfield, a suburb of Bristol, England. Here are 10 CG Did-You-Knows:

- Grant’s parents worked in the garment industry—his father as a tailor’s presser; his mother as a seamstress. His older brother, William, died very young of tuberculous meningitis.

- Grant showed an interest in performing at a very early age, and his mother, who was otherwise very cautious regarding his upbringing after the death of his older brother, encouraged him in pursuing this interest.

- When Grant was just nine years old, his father had his mother placed in a mental institution, telling Grant she was away on holiday. He later told Grant that his mother had died—she had not. Grant didn’t learn she was still alive until twenty years later.

- By his early teens, Grant was performing as a stilt walker with a touring group of acrobats. When he was 16, the troupe traveled to New York City, where it enjoyed nine-month run at the Hippodrome—at that time the largest theatre in the world—before touring the country in vaudeville.

- When the time came for the troupe to return to England, Grant and a few of his fellow performers decided to remain in the U.S. Grant returned to NYC and continued to work, first in vaudeville and then the legitimate theatre, which eventually led to a contract with Paramount Pictures. He made his debut in 1932 in a comedy called This Is the Night that also starred Lili Damita, Charles Ruggles, Roland Young and Thelma Todd.

- Douglas Fairbanks was a key role model for Grant, who shared the star’s good looks and athleticism (Grant had met Fairbanks aboard ship when he first crossed the Atlantic bound for NYC).

- Ian Fleming is said to have based the character of James Bond in part on Grant (we think he’d have made a great Bond), and Raymond Chandler once wrote, “If I had ever an opportunity of selecting the movie actor who would best represent [Philip] Marlowe to my mind, I think it would have been Cary Grant.”

- A telephoned complaint from Grant, who was staying at the Plaza Hotel in NYC, to Conrad Hilton, who was in Istanbul at the time, convinced the hotel czar that the Plaza should serve two full English muffins with room service breakfasts, rather than the one-and-a-half they had been serving.

- Grant donated his entire salary of $137,000 from The Philadelphia Story (1940) to the British War Relief Fund. Four years later, he donated his salary of $160,000 for Arsenic and Old Lace to British War Relief, the USO and the Red Cross.

- Grant was a big fan of Elvis Presley and can be spotted in the audience and backstage in Presley’s concert documentary Elvis: That’s the Way It Is (1970).

Happy birthday, Cary Grant, wherever you may be!