Old movie buffs know that, if you’re watching a picture from the 1920s or early ’30s and it’s set in NYC, there’s a better than even chance there’ll be a scene set at Coney Island.

Old movie buffs know that, if you’re watching a picture from the 1920s or early ’30s and it’s set in NYC, there’s a better than even chance there’ll be a scene set at Coney Island.

And whether those scenes are filmed on a backlot, at a Southern California stand-in amusement park, or, as is sometimes the case, at Coney Island itself, they generally preceded by a scene-setting montage of stock footage shot at Brooklyn’s “Sodom by the Seashore.” You can generally count on seeing some shots of Luna Park and often Steeplechase Park, too, as well as some funhouse footage, with those spinning tubes customers are asked to walk through, the rotating platters they try to avoid being spun off of, and those large slides that were navigated while sitting on a potato sack.

(By the way, it pleases us greatly to recall the funhouses of our own youth and realize that they boasted the same basic features the funhouses of the 1920s did. I suppose there are still funhouses like that around today, but we don’t know where they are. Readers?)

What one doesn’t often see in these montages, though, is footage of those aspects of Coney Island that are still extant today. After all, the original Luna Park is long gone; Steeplechase Park, too. But the iconic rides that still exist—the Wonder Wheel, the Parachute Jump (which is no longer functioning but still stands watch over the surrounding festivities, a landmarked monument)—are rarely seen in these montages.

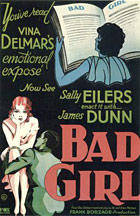

But while watching Bad Girl, a 1931 NYC-set drama directed by Frank Borzage and starring Sally Eilers, James Dunn and Minna Gombell, the other night, we were tickled to see not only the familiar shots of Luna Park and funhouse footage, but a lingering shot of the Cyclone, an old-school roller coaster that debuted in 1927 and is still rattling bones today. The Cyclone, a beloved Coney Island institution, was designated a New York City landmark in 1988, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991. But we don’t think we’ve ever seen it depicted in an old movie. Other Coney coasters, yes, but never the Cyclone.

Here’s the montage we’re speaking of:

If you’ve never taken a spin on the Cyclone, it’s time you did. You’ll exit the ride a bit wobbly-legged and perhaps just a little queazy, but you’ll know you’ve experienced the real deal in the world of roller coasters.