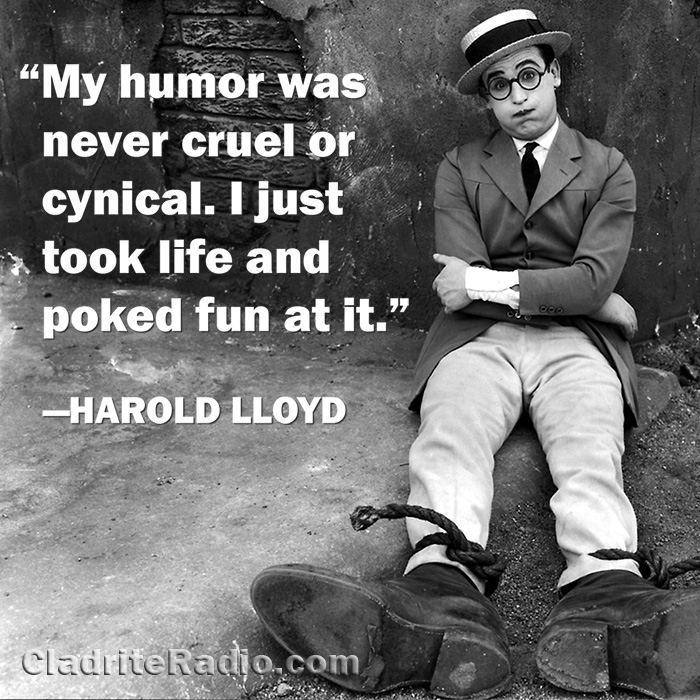

Comedy giant Harold Lloyd was born 124 years ago today in Burchard, Nebraska. Here are 10 HL Did-You-Knows:

- Lloyd’s parents fought frequently when he was a child (due in large part to his father’s penchant for launching unsuccessful, short-lived businesses); they divorced when he was a teenager, after which Lloyd and his dad moved west to San Diego. In 1912, Lloyd, who’d acted on stage since childhood, began to work in one-reel comedies for the Thomas Edison company. His first role was a Yaqui Indian in short called The Old Monk’s Tale.

- Before long, Lloyd moved to Los Angeles, where he became friends with aspiring filmmaker Hal Roach. Roach told Lloyd that when he was able to produce his own pictures, he’d make a star out of Lloyd. When Roach opened his studio in 1913, the pair began to collaborate on creating Lloyd’s first recurring role, Lonesome Luke, a character influenced greatly by Charlie Chaplin‘s Tramp.

- Within a few years, Lloyd began to shift toward the character that is better remembered today, often referred to as the “Glass character” for the round specs that he wore. “When I adopted the glasses,” Lloyd said in a 1962 television interview, “it more or less put me in a different category because I became a human being. He was a kid that you would meet next door, across the street, but at the same time I could still do all the crazy things that we did before, but you believed them. They were natural and the romance could be believable.”

- In his Lonely Luke days, Harold Lloyd gave actress Bebe Daniels his start. The credits usually listed Lloyd’s character as “The Boy” and Daniels’ as “The Girl.” The pair were romantically involved for a time. After five years, Daniels went on to a very successful career as a leading lady. Daniels’ replacement in Lloyd’s pictures was Mildred Davis, whom he wed in 1923. They were married until her death in 1969.

- In 1919, while shooting some publicity photographs, Lloyd suffered extensive damage to his hand while lighting a cigarette with a prop bomb that he thought was just a smoke pot. The bomb exploded, and Lloyd lost his thumb and forefinger. He also suffered burns on his face and incurred damage to one of his eyes (luckily, his sight was unaffected).

- Lloyd and Roach began focusing on feature-length pictures, rather than shorts, in 1921, and when the pair parted ways in 1924, Lloyd launched his own production company.

- Though Buster Keaton and Chaplin are today considered the greatest comedians of the silent era, in the 1920s, Lloyd’s pictures made more money than either (in large part because he was so prolific—he made 12 full-length features in that decades to Chaplin’s four).

- In the late 1920s, Lloyd built a home in Beverly Hills he called Green Acres that boasted 44 rooms, 26 bathrooms, 12 fountains, 12 gardens, and a nine-hole golf course. Though the surrounding grounds have been subdivided, the main house and the estate’s principal gardens are still there, and the estate is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- It’s been reported that Lloyd was approached to portray Elwood P. Dowd in the original Broadway production of Mary Chase’s play, Harvey. When Lloyd turned the part down, the role went to Frank Fay.

- Lloyd’s post-cinema hobby was 3-D photography; among his works were portraits of Hollywood stars such as Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne, Sterling Holloway, Richard Burton and Roy Rogers. He also shot a good many nude…er, artistic photographs of more anonymous starlets of the day.

Happy birthday, Harold Lloyd, wherever you may be!