Charles Ray was a popular juvenile star in the 1910s and ’20s, but by the ’30s, his career was on the rocks, and he turned to writing. Here’s another in a series of offerings from his book, Hollywood Shorts, a collection of short stories set in Tinseltown.

Charles Ray was a popular juvenile star in the 1910s and ’20s, but by the ’30s, his career was on the rocks, and he turned to writing. Here’s another in a series of offerings from his book, Hollywood Shorts, a collection of short stories set in Tinseltown.An hour before dawn the east-bound Limited stopped briefly at Cherokee Junction, left two passengers, then wound on snake-like into the night.

Joseph Dillon guided emotional wife across a snow-covered platform, mumbling vile oaths of dissatisfaction against the snow, the cold, and everything in general.

“Oh, please don’t, Joe!” his wife moaned through chattering teeth. She placed a handkerchief over her mouth and talked through it. “You only make me feel worse when you rant on at every little thing.”

“Rant? God, why shouldn’t I? What is there left to live for? You tell me. Everything is black. It’s the end.”

Irritably he swung his wife toward a dismal-looking sign which, with yellow winks, proclaimed sardonically: Quick Lunch.

“Get a load of that greasy beanery!” Joe derided.

Failure in Hollywood was horrible enough, but the loss visited upon him the day before cankered his soul. Now the slip-slide progress across the icy bricks only goaded him on to further blasphemy.

“Joe, were both our trunks put off that baggage car?”

“Say, have you gone nutty? You stood right there with me, watchin’. What in hell are you askin’ such a question for?”

“Don’t know. Wanted something to say, I guess. Every now and then my thoughts get beyond my control, and I just have to talk.”

She stood shivering while he held the lunch-room door open against a north wind which challenged all his strength.

The warm air of the small room quickly changed the chemistry of Joe Dillon’s body, but not his distorted mind. Banging heavily upon the counter, he threw a hateful flock of words toward the kitchen, demanding service.

“Joe, don’t act that way. We’ve got to go on living just the same. I guess we do,” she corrected with mystery in her tone. Then her eyes went instantly moist.

“Aw, nuts!” Joe scoffed, then bellowed, “Coffee!” like a sideshow barker.

“Stop it, Joe! I’m trying to take the blow bravely. He was my baby as well as yours!”

“Sorry I can’t take it so well!” Joe barked back, hissing distaste through set molars. “What a God-forsaken world this is! No money to give it a decent burial. How do you suppose I feel, havin’ a kid o’ mine buried out here in the wilds? And what a life for us to live! Us who should be somethin’, bobbin’ about the country, playin’ dinky vaudeville dates to numbskulls who don’t know a swell act when they see one. What a life! God, what a life! What a—“

“Now listen, Joe., I can’t stand any temper today! I just can’t!”

She relaxed her elbows on the counter and covered her eyes with her hands, while her husband raved on without restraint, ready to hurl a decanter on sight of a truant waiter.

Presently a middle-aged man descended the tiny stairs leading to the mezzanine floor. He mumbled low-toned apologies as he wiped steamy-looking eyes with the corner of his apron.

Half locking his temper up to please his wife, Joe demanded, “Coffee!” with accusations in his tone.

“Only a minute or two,” the waiter returned in a kindly voice. “I’m a little late this morning, but it won’t take long now that I’ve got myself together.”

Through tightly drawn slits, Joe watched the waiter’s exit and sneered: “Imagine a waiter havin’ to get himself together? Numb, that’s what that guy is from the ears up, like all the yokels in this part of the country!”

“Be tolerant, Joe. Be grateful that you’ve got a warm place to wait. The local won’t be along for an hour.”

“But didn’t the mug know a train was due? Shoulda had coffee ready! The railroad company oughta pull his license from him. I’ll tell him plenty when he pops his funny head in here again with that prop smile on his dead pan. Bet he’s the kind of a waiter who says: ‘If you like our service, tell others. If not, tell us.’ Aw—“

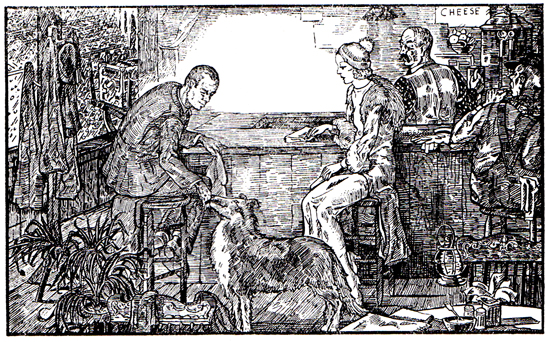

He curled his lips to make an unpopular sound when his eyes fell upon a collie dog descending the tiny stairs. Like a convert, Joe exclaimed:

“God, what a beautiful collie! Just like the kid’s!”

Messenger-like, the dog made its way to the customers, placing a damp nose of affection in each of their hands. Then as if asking some question through sad eyes, it raised a gentle paw to Joe’s knee.

“Catch that?” Joe said fervently as his mind shot back a year. “Just like the kid’s dog used to do. Whaddya s’pose it’s tryin’ to tell me? Somethin’ important, I bet.”

The waiter swung in from the kitchen with steaming water for the coffee urn.

“My, he’s the very image of our collie back home,” the wife said, just to make conversation. “We got one for our baby when it was two. That breed of dog just seem to know everything, doesn’t it?”

“Yes, it does,” the owner replied, adjusting the blaze under the urn. “The dog ,nows that something’s the matter. That’s why it’s so sad. My little boy died last night. He’s so still and white on his bed upstairs that the dog don’t know what to make of it. We generally have a big romp at this hour, waitin’ for the Limited that just dropped you off.”

He straightened up from the urn, questioningly.

“Do you know much about collies? Mine won’t eat a thing. All it does is go up and down them stairs and whine. I’ve heard of that story about love birds starvin’ themselves if—but I don’t think that a collie would. Say, I remember somethin’ in the ice box that might tempt him.”

Hurrying toward the kitchen, he talked as he went, assuring good coffee in another few minutes.

Silence weighed down heavily.

The dim lights in the room went dimmer through the mist over Joe’s eyes. An awful surging emotion in his bosom forced him to slip from the stool at the counter and draw very near to his wife. When he found voice, he implored:

“Anna, I can understand how you have been able to take the blow of our kid’s death, but,” he cleared the huskiness from his throat, “I can’t understand how you’ve been able to stand for me. Don’t answer me now or I can’t take it, but from now on I want you to know that it’s a new page with me. If you think you can forgive the past, why, you’ll never have to mention my temper or any of my terrible habits again.”

Her hand ran along the counter edge until it touched her husband’s, where she left it in the strength of his grasp.

The waiter emerged from the kitchen with a saucer of choice morsels. He was very much surprised when the collie began eating from the hands of the customers, as if it had known them always.

After serving the pair, the waiter drew coffee for himself and sat near them, seeming grateful for companionship, though he said little.

Silently they all communed together while watching the dawn of a new day chase the darkness from the snow-covered junction. When the local clanged in, they exchanged a toneless farewell, profuse with outward-bound gestures of courage.

A starved-looking author leaned across a shiny mahogany desk with eyes upon a motion-picture supervisor.

“What do you think of that for a story, Chief?” he asked nervously.

“Naw, no good!” the producer grumbled. “THere’s no scenario in it for my money. How can you make a picture with material that’s so heavy? There’s no comedy relief at all. You’ll break people’s hearts and the boxoffice at the same time with stuff like that.”

The author began, “Well—” gulped, and stuttered: “But that’s only one of my stories. I’ve been ill so long that I have written quite a number. Here’s one I think you’ll like because of its humor. If you have time, I’d like to read part of it. I’ll read quickly, then tell you the rest. I call it:

Bill was fat and congenial, and Mamie was thin and calculating.

“I love you, Mamie,” Bill said religiously, each time he left her front steps.

Bill Splivin was a bond salesman. Mamie Conti worked extra in motion pictures. Ever since he could remember, Bill had had a yen to marry an actress. Thinking Mamie one had caused him to propose continually.

One night when he was leaving her front porch, Mamie said: “Okay, Bill, but I might as well tell you that I couldn’t possibly have the slightest interest in marrying a man who had anything to do with liquor.”

While edging down the stairs, Bill made a firm decision.

“I’ll quit drinkin’!” he blurted out, surprising her somewhat. “And that’s not all. I’ll change everything you’ve said you don’t like in me. I got a temper that’s vile, and I know it. I’ll change that, too. Yep, have a good house-cleanin’. Now, how’s that for a flock of resolutions?”

Flippantly Mamie returned: “You gotta show me!”

“I will! I’ll start from this very night. I won’t see you again until I’m cured of the liquor habit. It takes a week to do it, they tell me.”

With a firm conviction, he skipped lightheartedly to his car.

There was courage in Bill’s soul, tingling from head to foot. His foot happily played a game of tag with the motor accelerator. The car fairly soared down the boulevard. Resolution had infused new life into him.

Yes, he’d go right away, he reasoned, and get booked at that what-you-may-call-it place, where they cure alcohol addicts. Within a week he could return and win Mamie’s respect and hand. Meantime, he’d concentrate a lot on his temper, conquer everything, in fact, and spread that Christian spirit also. Why hadn’t he thought of doing it before?

The car sped faster and faster with each new decision.

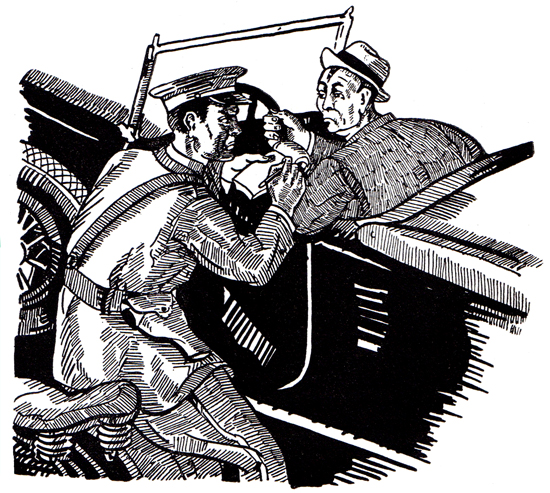

The purr of a motorcycle alongside gave him goose pimples. “Pinched!” he grumbled through gritting teeth. It always gave him goose pimples to hear one of those slippery eels of a cop edging alongside, and to see him twist in front with his arrogant wave of authority.

new line to spout when you get caught for speedin’? Lemme look at your license card.”

Meeting every rough insinuation with grunts, Bill held his temper and wondered, not a little, why the officer hadn’t returned his Christian-like spirit.

After presenting the ticket, the cop bellowed, “Get a new line,” mounted his mechanical steed, and whizzed off for the foxy hunt.

Quite suddenly, Bill experienced a new thrill. He had used diplomacy for the first time in his life. He had used grunts instead of curses; had won a battle which he had never thought of fighting before this eventful night. The night took on a radiant hue, and the evening breeze cooled his remaining temper. Exhilarated by the achievement of such self-control, he sped down the boulevard in ecstasy.

Again the purr of a motorcycle alongside gave him goose pimples. His flesh quivered, and his stomach heaved at the thought of being presented with another speed ticket from the same officer in less than five minutes.

“Over to the curb!” came a caustic command.

Desire to curse the ambusher was squelched by thoughts of Mamie. Through chattering teeth, he forced a pleasant-sounding answer, full of lawful respect.

“I’m sorry, officer,” he finished meekly.

“Sorry!” the cop thundered. “Why, the judge’ll crucify yuh when he finds yuh with two tickets. Yuh don’t seem to learn, do yuh? Didja ever go to school? Better try a drivin’ school!”

“And you can’t overlook it just this once, officer?”

“Naw! I hope the judge says: ‘Jail!’ You deserve it!”

“Why, you son—why, you sum up things awful funny!”

With fists opening and closing in deep desire, Bill regretfully thought that trying to be a Christian was too much. His eyes closed; he counted up to ten several times. When he opened his eyes again, an inscribed ticket was waiting under his nose.

His attitude and silence were misunderstood.

“What’s the matter this time?” the cop growled. “You’re not entertainin’ me with any bedtime stories. What’s the big excuse you’ve thought of? Let’s have it, I need a laugh.”

“Love,” Bill answered like a convert, shocking him. “Love made me speed tonight, because I was so happy. Love kept me silent when I wanted to curse you, call you dirty names, and beat you up. Love did all that,” he concluded forcefully. “And now you can go to hell!”

“Boy, that’s a new one I ain’t never heard yet!” While testing his motor, the officer shook with laughter. On moving into traffic, he yelled back: “Sorry I can’t tear up that ticket. You deserve to have it killed.”

Many red stop-signals grinned at Bill along the boulevard, but he was as alert to them as he was to his motor speed. He moved along like a snail and finally drew up in front of a building declaring its cure for alcoholism. Its dark doorway, however, informed him that a new day would have to dawn before he could enroll.

“God—I mean, gee,” Bill corrected quickly. “I wanted to sign up tonight for the whole works, tuh keep outa temptation’s way. Now ain’t that hell—I mean, awful. There ain’t nothin’ to do, or no place to go.”

Then the devil took possession of Bill Splivin.

Lightning-like, he thought: I’ll go over to Harry’s Bar, but his resolution screamed “No!” right back at him.

“H-m,” Bill mumbled, and thought: This resolution stuff is too much for me. I bet I don’t make it! Goin’ saint certainly plays hell with a guy!

He drove slowly down the street, very slowly, and turned at a certain corner, hardly conscious of the direction.

“I’ll just go over to Harry’s Bar for a minute or two,” the devil argued for Bill. “Have a coupla drinks, and—“

“No!” a saint in the form of Mamie condemned.

“Well, then, I’ll just go over an’ not having anything to drink,” Bill argued on his own. “No harm in jus’ goin’ over. See the bunch, whoever’s there. No harm in jus’ goin’ over. The gang’ll be glad to know about this decision on reform.”

“Sure, they’re all nice, sympathetic boys. Now there’s a firm decision,” the devil made him reason.

His foot on the gas responded to the diabolical urge.

At nine o’clock the next morning, Bill Splivin was hanging on to Harry’s Bar with a weak hand. Two pals had sympathetically helped him celebrate “going on the wagon.” They were loyal boys; had kept vigil all night, just to be sure Bill got to the what-you-may-call-it cure place on time.

Ed Harris, now sagging a little at the hips, announced: “S-nine klock, Bill. S-time tuh book yuh at th’ call-it place.”

Ned Bates wasn’t quite so cockeyed. He could talk straight, stand straight, and almost see straight.

“Yep,” he urged, “we gotta give you up, Bill, though we hate it, for seven whole days, while they make you sick of liquor, vomit, and get cured. Let’s get goin’.”

“But we’re seein’ yuh through!” Ed declaimed.

“Right!” Ned exclaimed, patting Bill’s shoulder. “An’ you’ll ‘member us, will yuh, when you’re cured? Now we’re goin’. Yep, goin’ tuh land you in state. We won’t even let yuh drive your own car. Any orders, pal?”

Bill lifted a shaking hand with a glass in it.

“M-mm las’ drink of anythin’ bud wadder,” he mumbled slowly.

It was interpreted correctly by Nick. Ed wasn’t sure of anything until he saw Nick leading Bill toward the street door. Then thought filtered through his numb skull, and he brought up the read in a wide, uncertain circle.

The cool morning air had a refreshing effect on Nick. He leaned Bill against the brick wall, advised deep breathing, and demonstrated with miniature calisthenics.

Two school girls passed quickly,giving wide berth, implying that they knew the difference between a man and the leaning Tower of Pisa.

“So what!” Nick sputtered toward the giggling girls, and led Bill to his car, pouring him into the tonneau.

Ed wasn’t much help. He waited on the curb until the car seemed to come around again; then he got in carefully.

“I’ll drive,” Nick advised thickly. “Hey, Ed! Hold Bill’s head. Don’t let it jerk off!”

While testing the motor violently, Nick thought of a possibility of having his own head held, probably by a trained nurse, if the kaleidoscopic effect before his eyes did not cease.

Back in the tonneau, Ed was patting Bill’s shoulder tenderly, cheerfully repeating, “Ol’ boy, ol’ boy, ol’ boy,” which, relative to nothing, even Einstein could not interpret.

The car started with a jerk. Cries from Bill caused Nick to kill the motor.

“Ed, what’s Bill yellin’ about back there? What’s he sayin’? Maybe it’s important.”

“He says you drr-ive.”

“Sure I’ll drive. Fast too, Bill. I’ll step on it an’ get you there in nothin’ at all.”

The thought of another ticket brought forth wild grunts from Bill, who could vision nothing but a judge and an electric chair.

“Oh, drive slow. I sure will, Bill. It’s your party. Anythin’ yuh want. I’ll put’er in low gear an’ keep it there all the way if it hurts your head to go fast.”

Gears ground, the car started easily. The extremely slow speed impressed the traffic officer at the corner. Ed’s position, hugging Bill, and the cockeyed look in Nick’s face caused him to assume that it was a pacing-car for an oncoming funeral. He whistled, stopping the traffic each way.

The car passed the intersection in that honorable respect extended to mourners.

Seven days later, Bill Splivin emerged from the cure, a new man in body and soul. He had fought a hard fight and had won. He would never touch liquor again. Now he could rush to Mamie, tell her how right she was, and claim her as his reward.

Jumping into his car like a juvenile, he sped down the boulevard toward the house of his desire.

With a firm hand, he stopped the car in front of Mamie’s house, which had so often wobbled its way about, took the steps two at once, and rang the bell vigorously while he whistled a few bars of The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise.

“Is it really you, Mr. Splivin?” the landlady gushed. “Have you been to Palm Beach or something? You look wonderful!”

Modestly accepted her compliments, Bill asked for his sweetheart.

“Oh, Mr. Splivin, ain’t you heard? Mamie’s married! Yes, she is! Eloped with that Mr. Wainto—whatever his name was. You know, the man who used to sell us the gin.”

Quite confused, Bill descended the steps. He sat meditatively in his car for a few moments, trying to grasp the situation. He wasn’t really crazy about Mamie, he analyzed; then mumbled:

“What a dirty trick to play on a guy. I’ve lost my taste for liquor.”

Looking hopefully up from his manuscript, the author eyed the producer.

“Can you use a story like that, Chief?” he ventured with salesmanship in his tones.

“I have a vision,” the producer smacked his lips. “We’ll blend the two stories into one. Tie up an interest between this fella in your story entitled, The Cure, with the woman in your story entitled, Onward Bound. Don’t make him a bond salesman. He’s a vaudeville agent, see? The two guys that get drunk with him all night are comics, get it? Now this girl Mamie is jealous of all the women in the first story. We’ll mix a little kidnaping up into it, but not on the level, see? Mamie gets the kid away from the mother and hides it, to teach the ol’ man a good lesson. Then we don’t have the heavy story stickin’ out like a sore thumb. And we’ll call the new draft, Love Bound. Quite a vision?” he asked as he got stymied, and turned to his telautograph to demand a scenario conference immediately after lunch.

Thrilled and speechless, the author was engrossed in a vision of his own; but not about the picturization of his blended stories. He saw the vision of ham and eggs, for a long time to come.