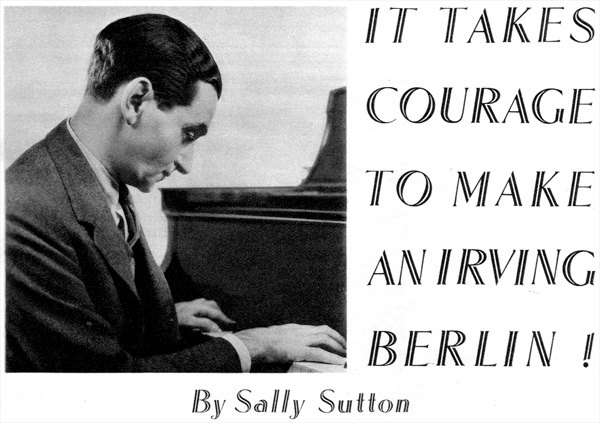

Is there a better known, more revered songwriter, even today, than Irving Berlin?

We think not.

But it’s intriguing to read the following profile, which dates from 1935. Berlin was already a giant in the world of music and theatre, but many of his greatest accomplishments still lay ahead of him.

In fact, of the dozens of titles of Berlin’s hit songs mentioned in this profile, very few were familiar to us (and we bet you’ll find them as unfamiliar as we did).

It was quite a life that Mr. Berlin led. And quite a career.

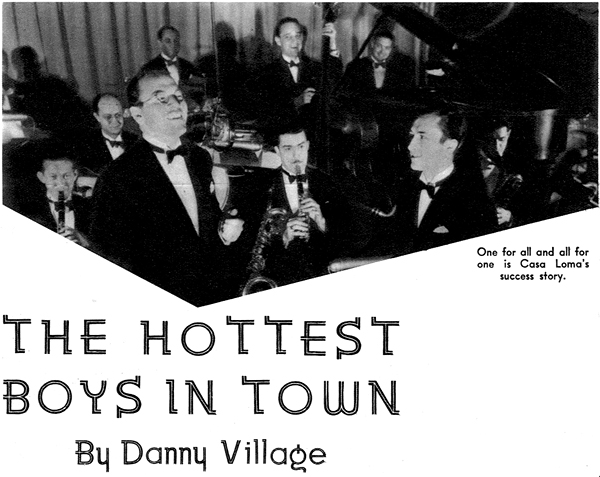

HE hottest boys in town are members of that rootin’, tootin’ outfit of blue-blowers called the Casa Loma orchestra. How they got their start made band history.

HE hottest boys in town are members of that rootin’, tootin’ outfit of blue-blowers called the Casa Loma orchestra. How they got their start made band history.