In Chapter 12 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée finally gets around to providing some typical memoir material, sharing tales of his boyhood in Westbrook, Maine, and offering accounts of his experiences traveling west to Hollywood to make his first picture, The Vagabond Lover (1929).

From Westbrook to Hollywood

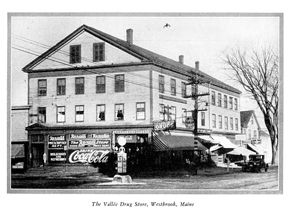

However, it was during my boyhood in Westbrook, Maine, that I first began to dream of the theatre. I must have inherited a love for all things theatrical from my father who, though a druggist all his life, had been associated with several theatres in various small business ways. Anyway it was always in the back of my head, and even when I was in the early grades of grammar school I used to climb up by the door of the motion picture booth and peek in to watch the film with fascinated eyes as it went past the aperture plate, with the bright light from the arc lamp shining on it; and the hum of the machine as the operator cranked it by hand, and the smell of film and film cement meant as much to me as the picture itself.

However, it was during my boyhood in Westbrook, Maine, that I first began to dream of the theatre. I must have inherited a love for all things theatrical from my father who, though a druggist all his life, had been associated with several theatres in various small business ways. Anyway it was always in the back of my head, and even when I was in the early grades of grammar school I used to climb up by the door of the motion picture booth and peek in to watch the film with fascinated eyes as it went past the aperture plate, with the bright light from the arc lamp shining on it; and the hum of the machine as the operator cranked it by hand, and the smell of film and film cement meant as much to me as the picture itself.