Frank Oscar Larson (1896-1964) was born in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, of Swedish immigrant parents and lived in Flushing, Queens most of his life. As an adult, Larson spent his days at a branch of the Empire Trust Company (now Bank of New York Mellon), working his way up through the ranks from auditor to vice-president, and spare time on weekends taking photographs of street life throughout New York City.

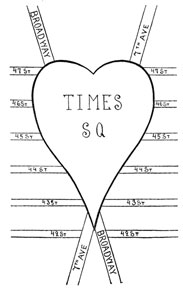

He was an accomplished photographer who eloquently documented 1950s Chinatown, the Bowery, Hell’s Kitchen, City Island, Times Square, Central Park, and much more.

This exhibition is compiled from thousands of negatives recently discovered stored away in his daughter-in-law’s house in Maine in 2009. Soren Larson, his grandson and a television news camera man and producer, has been scanning and printing the 55-year-old images found stored in over 100 envelopes filled with mostly medium format, 2-1/4 x 2-1/4″ negatives, and neatly noted by location and date in Larson’s own hand.

Frank Oscar Larson: 1950s New York Street Stories is on view at the

The above text is from