Here are 10 things you should know about George Raft, born 119 years ago today. Raft is arguably as well known today for his association with mobsters as he is for his movies.

Tag: Maxim’s

Happy 115th Birthday, George Raft!

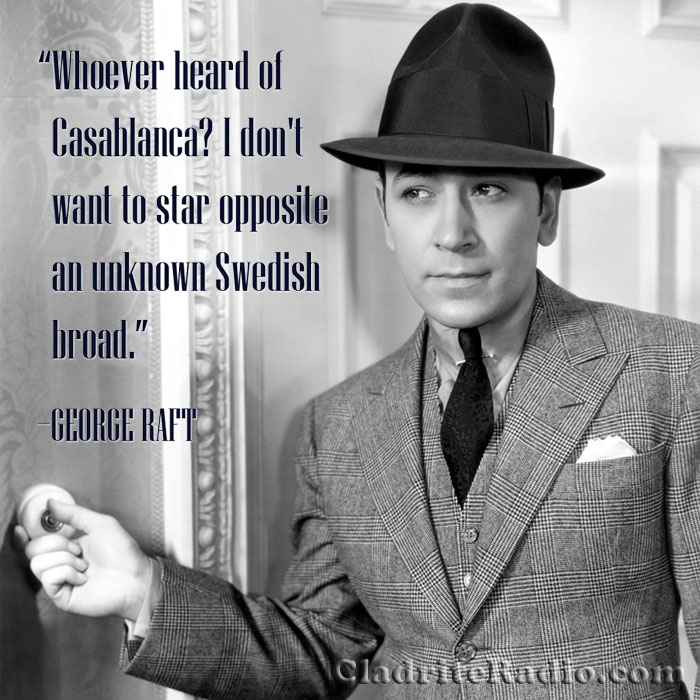

Actor George Raft was born George Ranft 115 years ago today in the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City. Raft is perhaps as well known today for the movie roles he turned down as those he accepted. Here are 10 GR Did-You-Knows:

- His parents were of German descent.

- From his youth, Raft took a great interest in dancing, and his skills as a hoofer would serve him well as he found his way as a performer. In his salad days, he made money performing (and dancing with the lady patrons) at establishments such as Maxim’s, El Fey (with Texas Guinan) and various other night spots.

- He married Grace Mulrooney, who was several years his senior, when he was 22. They separated early on, but never divorced (perhaps because Raft’s family was Catholic), and he supported her until she died in 1970.

- Raft was known to run with a pretty rough crowd. He was childhood friends with gangsters Owney Madden and Bugsy Siegel; Siegel stayed at Raft’s home in Los Angeles when the gangster first moved there.

- Raft reportedly turned down the lead roles in High Sierra (1941), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1942) and Double Indemnity (1944). The first three of those roles proved to be great successes for Humphrey Bogart.

- Raft appeared in Mae West‘s first (Night after Night, 1932) and last (Sextette, 1978) pictures.

- In James Cagney‘s autobiography, the actor wrote that Raft prevented Cagney from being rubbed out by the mob. Cagney was president of the Screen Actors Guild at the time, and the story goes that he was adamant the Mafia wouldn’t become active in the union’s affairs, which was not a popular stance in certain circles.

- Raft was a lifelong baseball fan, attending the World Series for 25 years in a row in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

- As a teen, Raft was a bat-boy for the New York Highlanders (later the Yankees).

- In the late 1950s, Raft worked as a celebrity greeter at the Hotel Capri, a Mafia-owned casino in Havana. He was there in 1959 when rebels stormed Havana to overthrow dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Happy birthday, George Raft, wherever you may be!

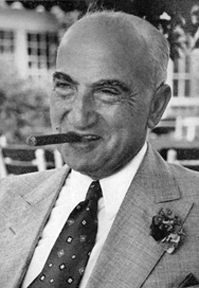

Formerly Famous: Julius Keller

Julius Keller’s primary claim to fame was his role as the man behind Maxim’s, a popular New York eatery that shamelessly borrowed its name from the venerable Parisian nightspot. Though he would be responsible for a number of restaurant and nightclub firsts, in his early years, one would have been hard-pressed to predict such success for Keller.

One of seven siblings, the diminutive Keller—he stated in his engaging 1939 memoir, Inns and Outs, that he stood just 5’ 3”—was born in Basle, Switzerland. Unbeknownst to his family, he emigrated to the United States at 16, arriving in NYC with fifty cents in his pocket.

It wasn’t long before Keller found himself scrambling for food and shelter, occasionally having to settle for a berth on a park bench. Finally, he secured a job at a bakery, earning $16 a month plus room and board. After subsequently working as a short-order cook and an oyster shucker, Keller took a job as a waiter at the Tenderloin’s Paisley House. From there he moved to the tony Gilsey House, though he was let go after spilling Lobster Newberg in the lap of Ada Rehan, a prominent actress of the day.

In the 1890s, Keller was a server at the city’s most acclaimed restaurant, Delmonico’s, furthering his education in the ways and whims of the rich and famous.

Keller was later hired at Louis Sherry‘s Casino at New Hampshire’s Narragansett Pier. It was there that he made his first lasting mark in the restaurant world. When the wife of hotelier Paran Stevens requested soft clams be served with her luncheon but offered no specifics as to how they were to be prepared, Keller presented her with a dish of his invention: Large clam bellies were baked on the half shell with butter, paprika, shallots, and a strip of bacon.

Mrs. Stevens loved the dish, and when she asked Keller what he called it, he quickly coined the name “Clams Casino,” in honor of his place of employ. Keller went on feature the dish at every restaurant he owned or operated thereafter.

Keller later owned a series of eateries of varying stature and quality. During those years, he augmented his income by running a bookmaking operation. For a while, he even served as proprietor of the Old Heidelberg, a bar that doubled as a house of questionable (if not downright ill) repute.

Keller also dabbled in politics during those years, tying in with Tammany Hall boss Charles F. Murphy. Keller was the driving force behind the Tammany-backed Gastronomic Political Club, which boasted 20,000 members—most of whom were restaurant workers. Keller even ran for the State Assembly, losing by just 250 votes.

Keller got back on a more reputable track when he and two partners took over the lease of a restaurant on 38th Street in a location that had proven over time to be cursed. A burst of inspiration for Keller is what turned the tide.

The Merry Widow was all the theatrical rage at the time, and because Maxim’s of Paris was featured in that comic operetta, Keller adopted the name for his new restaurant. Keller even dressed his staff in faux Old World attire, as did the Paris Maxim’s.

Read More »