Here are 10 things you should know about Thelma White, born 112 years ago today. Hers was a modest career, but she achieved a certain degree of lasting fame with her role in a popular cult film.

Tag: Lorenz Hart

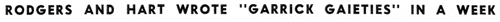

Remembering Richard Rodgers on His Birthday

10 Things You Should Know About Dick Foran

Here are 10 things you should know about Dick Foran, born 112 years ago today. He was a singing cowboy in “B” westerns and a supporting player in other pictures.

A dream that can be heard

Lyricist Lorenz Hart would be a spry 117 years old today, if he’d managed to stick around. He died far too young, at the tender age of 48 in 1943, and the loss was truly ours, for he had already penned words to accompany an astonishing array of classic melodies written by his partner in standards, Richard Rodgers—“Blue Moon,” “The Lady Is a Tramp,” “Manhattan,” “Where or When,” “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered,” “Falling in Love with Love,” “My Funny Valentine,” “I Could Write a Book,” “This Can’t Be Love,” “With a Song in My Heart,” “It Never Entered My Mind”—and who knows what additional musical magic he might have created, had he been given the chance?

Lyricist Lorenz Hart would be a spry 117 years old today, if he’d managed to stick around. He died far too young, at the tender age of 48 in 1943, and the loss was truly ours, for he had already penned words to accompany an astonishing array of classic melodies written by his partner in standards, Richard Rodgers—“Blue Moon,” “The Lady Is a Tramp,” “Manhattan,” “Where or When,” “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered,” “Falling in Love with Love,” “My Funny Valentine,” “I Could Write a Book,” “This Can’t Be Love,” “With a Song in My Heart,” “It Never Entered My Mind”—and who knows what additional musical magic he might have created, had he been given the chance?

One of our favorites, “Isn’t It Romantic?”, was written for the delightful 1932 musical, Love Me Tonight (1932), which was directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starred Maurice Chevalier and Jeannette MacDonald. Enjoy the following clip, which presents the song as it first appears in the picture.

![]()

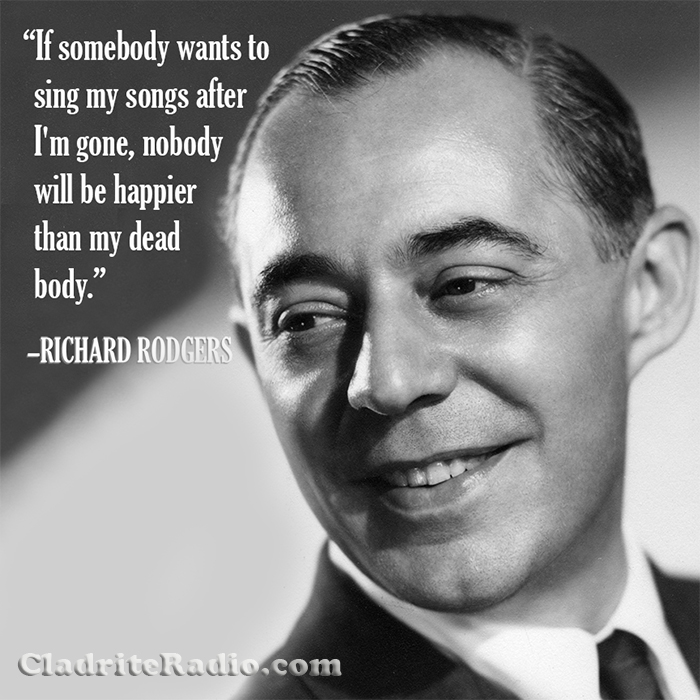

Snapshot in Prose: Rodgers and Hart

This week’s Snapshot in Prose visits a pair of classic composers who need no introduction, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, when they were at their most successful.

The author of the story speaks to both men, and we learn that they were of very different temperaments, outlooks, and lifestyles. Apparently musical theatre, like politics, makes for strange bedfellows.

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.