Jeanette MacDonald is best remembered today for the old-fashioned (even then) musicals she made with Nelson Eddy, but you’d be hard-pressed to get us to watch one of those. We greatly prefer the movies she made in the early Thirties—most notably with director Ernst Lubitsch—when she was allowed to show a little spark and sass on screen.

This profile originally saw the light of day in September 1940. Her professional pairing with Eddy was already well established, and she had been married to actor Gene Raymond for three years. She and Raymond remained married until MacDonald’s death in 1965.

The Private Letters of Jeanette MacDonald

The correspondence of a

movie star covers dozens

of different matters. Here

is your chance to spend a

day at Jeanette’s desk and

see how she deals with

this important problem.

By SONIA LEE

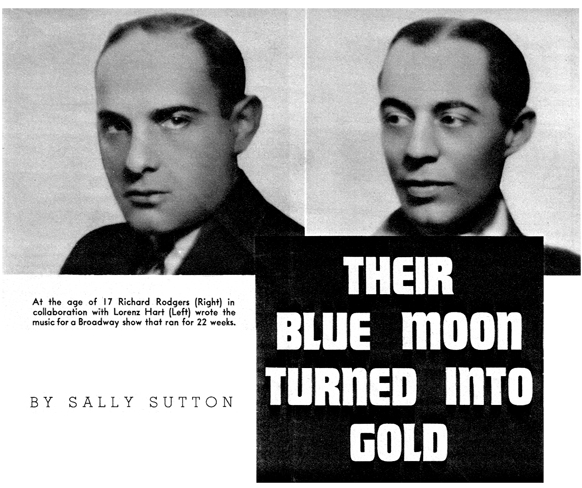

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.

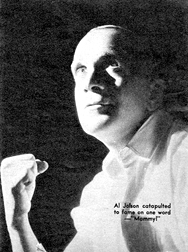

“MAM-MY! Mam-my!” boomed the great, heart-to-heart voice of Al Jolson, and the whole world shouted, “Here I is!”

“MAM-MY! Mam-my!” boomed the great, heart-to-heart voice of Al Jolson, and the whole world shouted, “Here I is!”

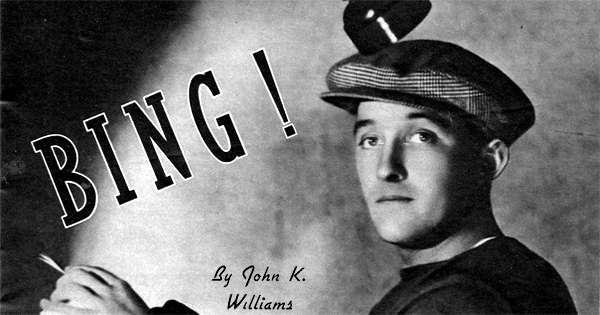

Bing Crosby will tell you that he is the laziest man in the United States, but it is doubtful if a more ambitious and energetic person ever fought his way to the pinnacles of success.

Bing Crosby will tell you that he is the laziest man in the United States, but it is doubtful if a more ambitious and energetic person ever fought his way to the pinnacles of success.